NOV 2016

www.ecs.org | @EdCommission

Many see education as the key to

future opportunity and success for

children of all backgrounds. However,

deeply entrenched inequities can

obstruct future opportunities and

successes for many American Indian

and Alaska Native students (hereafter

referred to as Native students).

2

These inequities are apparent in the

substantial achievement gap

that exists between Native students

and their white peers. On national

reading and mathematics exams,

Native students perform two to

three grade levels below their white

peers.

3

Additionally, Native students

face myriad diculties outside of

the classroom, including high levels

of poverty and challenges with both

physical and mental wellness.

Despite these problems, opportunities

exist for action that could positively

impact educational outcomes for

Native students. This report provides

an overview of the major education

issues the Native student population

faces and the current policies that exist

to address those issues at the federal

and state levels.

ESSA provides new

opportunities for states to

consider when enacting

legislation aecting Native

students.

Native students perform

well below their white

peers on national reading

and mathematics exams.

1

State and Federal Policy:

Native American youth

ALYSSA RAFA

POLICY

ANALYSIS

FOCUS IN.

Study up

on important

education policies.

ONLY 8 PERCENT OF

NATIVE STUDENTS ATTEND

FEDERALLY RUN SCHOOLS

THROUGH THE BUREAU OF

INDIAN EDUCATION, WHILE

THE REMAINING 92 PERCENT

ATTEND PUBLIC SCHOOLS.

Related Education Commission

of the States reports:

State and Federal Policy:

HOMELESS YOUTH

State and Federal Policy:

MILITARY YOUTH

State and Federal Policy:

INCARCERATED YOUTH

State and Federal Policy:

GIFTED AND TALENTED YOUTH

2

POLICY ANALYSIS

www.ecs.org | @EdCommission

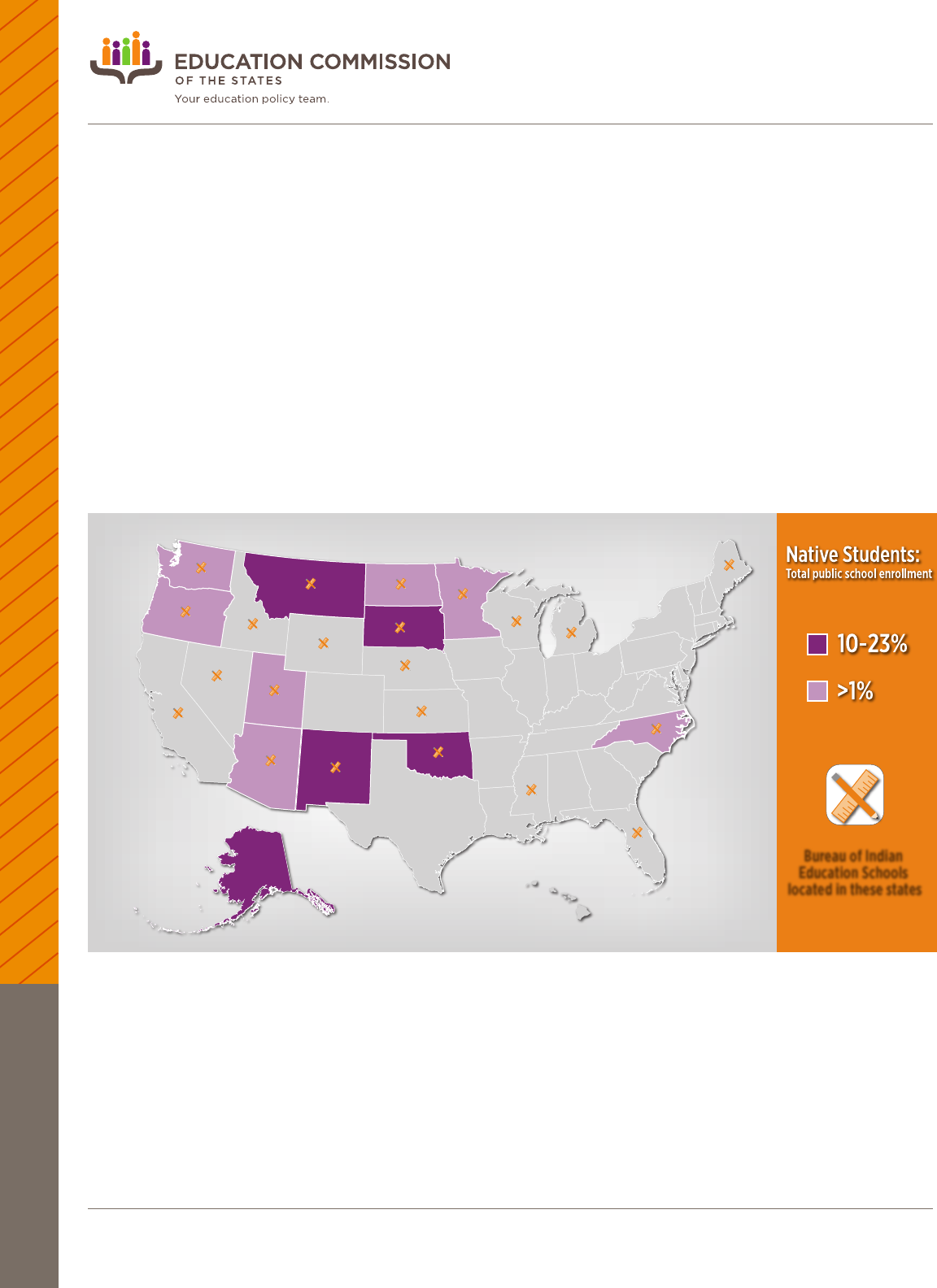

Who are Native Students?

The federal government defines Native students as “a member or descendent of an Indian tribe or band, or

an Eskimo, Aleut, or other Alaska Native.”

4

Native students comprise about 1 percent of the national student

population. The Bureau of Indian Education (BIE),

5

the federal entity charged with providing education

opportunities to Native students, currently oversees 183 elementary and secondary schools on 64 reservations in

23 states, serving a total of approximately 41,000 students.

6

However, in recent years, this number represented only

8 percent of the total Native student population. The remaining 92 percent are educated within the public school

system.

7

Of those students attending public schools, more than 50 percent attend low-density public schools, or

schools where less than 25 percent of the students are Native students.

8

Significant regional dierences in where Native students attend school also exist. The vast majority of Native

students reside in 12 states, with the largest concentration of Native students in Alaska, Oklahoma, Montana, New

Mexico and South Dakota.

9

In these five states, Native students represent between 10-23 percent of the total

elementary and secondary school enrollment.

10

Bureau of Indian

Education Schools

located in these states

Education Challenges for Native Students

From diculties with school readiness to struggles with graduation, Native students face many challenges. Data on

educational outcomes demonstrate disparities between Native students and their non-Native peers. In 2011, just 22

percent of Native fourth graders scored at proficient or advanced levels in mathematics on the National Assessment

of Educational Progress (NAEP), compared to the national average of 40 percent.

11

Reading performance on the

NAEP improved for every other major ethnic group between 2005-2011, but Native students saw no such gain.

12

3

POLICY ANALYSIS

www.ecs.org | @EdCommission

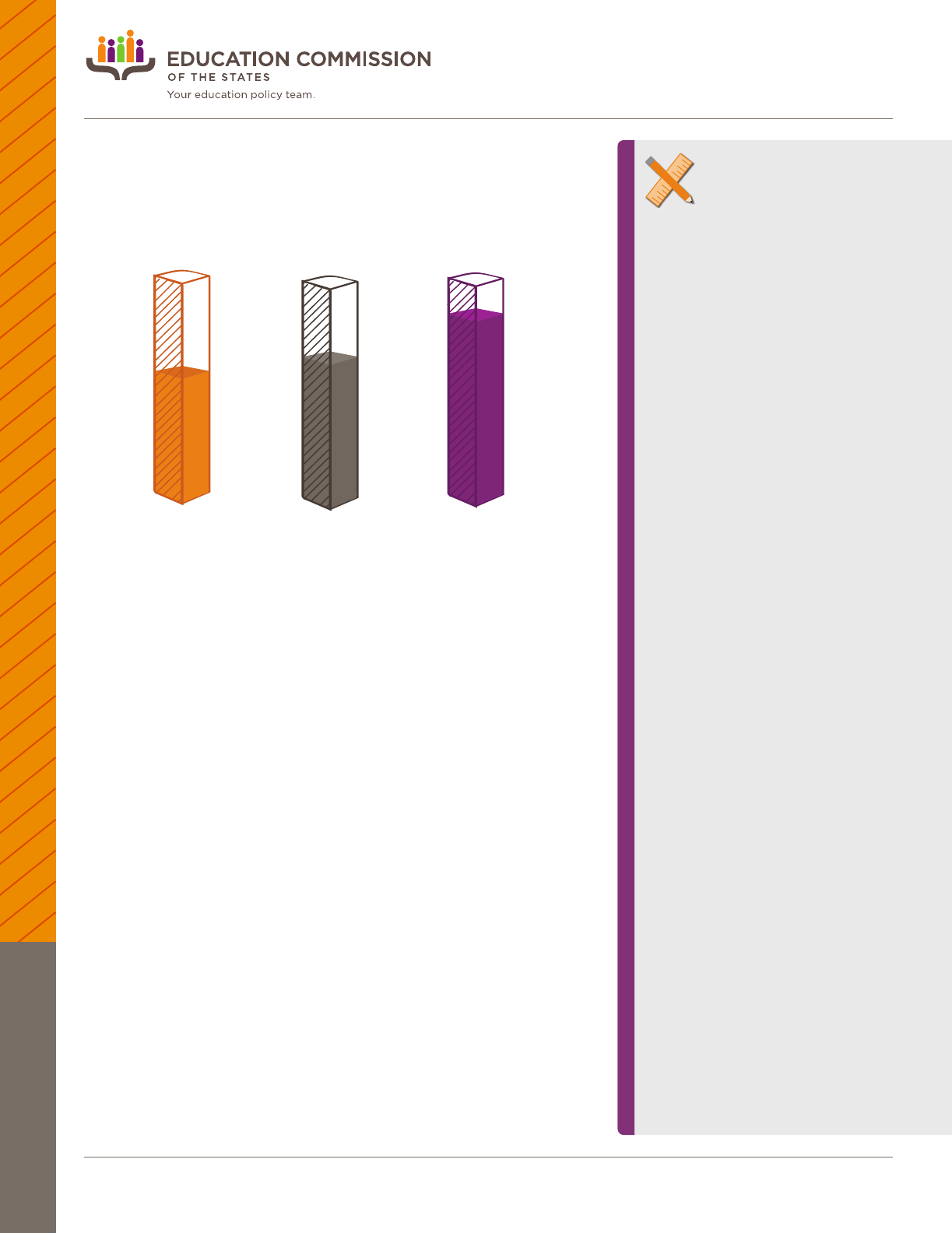

Perhaps most startling is the Native student high school graduation rate

which, at 67 percent in public schools and 53 percent in BIE schools, is far

lower than the national average of 80 percent.

13

FIGURE 1: GRADUATION RATES

53%

Native Students

in BIE Schools

80%

U.S. National

Average

67%

Native Students

in Public Schools

In addition to disparities in educational attainment, Native students

often face extreme poverty, as well as physical and mental health issues.

According to a 2014 report issued by the White House, more than one in

three Native children live in poverty, and suicide rates among 15-24-year-

old Native youths are 2.5 times the national rate.

14

States that are considering enacting policies geared toward addressing

these educational disparities should be aware of the significant issues

facing this population. The aforementioned White House report also

outlined some of the key factors associated with these disparities.

15

Those

key factors include lack of genuine tribal control, challenges in recruiting

and retaining highly eective teachers and school leaders, and lack of

Native languages and cultures in schools. Since the vast majority of Native

students attend public schools, it is important that policymakers consider

both state-level options for policy action, as well as the guidance,

programs and funding provided by the federal government under the

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

Approximately 8 percent of Native

students attend schools administered

by the BIE, under the U.S. Department

of the Interior. The U.S. Department

of the Interior is in the process of

re-designing the BIE, as they attempt

to shift it from a direct provider of

education to a capacity-builder and

service-provider to tribes with BIE

funded schools.

18

The U.S. Department

of the Interior set several goals for

this re-design, including strengthening

and supporting the eorts of

tribal nations to directly operate

schools funded by BIE, recruiting

and retaining highly eective

teachers and principals in those

schools, and fostering partnerships

between parents, communities and

organizations.

19

Under ESSA, the BIE can determine

whether the requirements established

by the U.S. Secretary of Interior

for standards, assessments and

accountability are appropriate for

their students. The BIE may apply for

a waiver and submit a proposal for

alternative standards, assessments

and/or accountability systems.

20

Additionally, BIE is now eligible

for discretionary funding that was

previously only available to states,

including grant programs for arts

education, community schools and

prevention and intervention programs

for at-risk youth.

21

BUREAU OF

INDIAN EDUCATION

4

POLICY ANALYSIS

www.ecs.org | @EdCommission

Federal Guidance under ESSA

Under the “Federal Government’s unique and continuing trust relationship with…the Indian people,”

16

the United

States government is responsible for the education of Native students. Title VI of ESSA provides further guidance,

with the aim of ensuring that Native students have access to high-quality programs that provide for basic

elementary and secondary needs as well as unique, culturally related academic needs.

17

While the federal government provides education to a small percentage of Native students through the BIE,

the responsibility to educate Native students does not lie solely on federally run schools. ESSA includes several

provisions that provide states with opportunities to improve educational outcomes for Native students. These

provisions include mandated tribal consultation, cooperative agreements, the permanence of the State Tribal

Education Partnership (STEP) and increased opportunities to institute Native language immersion programs.

Meaningful Consultation

Among other purposes, the “meaningful consultation”

22

provision of ESSA is intended to improve collaboration

between the entities invested in providing high-quality educational experiences to Native students. When

developing state plans for Title I funding, ESSA requires states to engage in meaningful consultation with tribes in

a timely manner. Additionally, local education agencies (LEAs) are required to consult with tribal education leaders

in their areas before submitting a plan or application for a covered program under ESSA or under Title VI. To ensure

compliance, tribes or tribal organizations must sign a written armation that consultation has occurred.

Cooperative Agreements

Under ESSA, states must coordinate with tribes in their eorts to support the education of Native students. The

“cooperative agreements”

23

provision of ESSA authorizes LEAs to enter into cooperative agreements with tribes

that represent at least 25 percent of that LEA’s Native student population. Additionally, other entities, including

tribes, are now eligible to apply for Title VI (Native American Education) funding originally intended for LEAs if the

LEA fails to establish a committee for the grant.

State Tribal Education Partnership

In order to promote expanded tribal control over the education of Native students, ESSA authorizes coordination

and collaboration of tribal education agencies (TEAs) with state education agencies (SEAs) through the STEP

program. Prior to the passage of ESSA, STEP was a pilot program. This program provides an opportunity for tribes

to develop a TEA through a one-time, one-year funding opportunity.

Native Language Immersion

ESSA provides federal grant funding in an eort to support the use, practice and maintenance of Native American

and Alaska Native languages. States may use grant funding for a number of purposes, including providing

professional development for teachers and sta, refining or developing curriculum and creating or refining

assessments written in the specific language of instruction. Through ESSA, tribes, TEAs, LEAs and BIE schools

are all eligible for grants, among other entities. Additionally, ESSA authorizes a study, to be conducted by the U.S.

Secretary of Education in collaboration with the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, to evaluate several factors related to

Native language education in schools and programs. The study will focus on the use of Native American languages

5

POLICY ANALYSIS

www.ecs.org | @EdCommission

to provide instruction, the assessment of academic proficiency in

Native languages, the level of expertise and experience available

within schools and student outcomes, including graduation rates.

State Policy Examples

Several states have enacted legislation aimed at improving the

education of Native students in their schools. Those policies generally

fall into four categories: collaboration between state and tribal entities,

teacher recruitment and retention, Native language instruction and

culturally relevant curriculum. Generally speaking, those states with

larger Native student populations tend to legislate more actively in

this area of policy.

24

As such, many of the examples below reference

legislation in those states.

Tribal-State Collaboration

In order to eectively serve Native students, and to comply with ESSA

requirements, it is important for state education leaders to consult

with tribal education leaders during their decision-making processes.

In recent years, several states have enacted legislation aimed at

improving collaborative eorts. State policies around tribal-state collaboration usually create venues, such as oces

and commissions, to facilitate the progress of this work.

J Utah created the American Indian/Alaska Native public education liaison position as a member of the

team supporting the superintendent of public instruction. The liaison and members of various tribes and

nations located in Utah are members of the American Indian/Alaska Native Education Commission, which is

charged with creating the American Indian/Alaska Native education state plan to address the educational

achievement gap and meet the educational needs of Native students in the state.

25

J Washington created an Indian education division, known as the Oce of Native Education, within the oce

of the superintendent of public instruction. The oce provides assistance to school districts to meet the

educational needs of American Indian/Alaska Native students.

26

J Through state legislation, Arizona authorized the creation of an Oce of Indian Education, as well as a

state Commission on Indian Aairs.

27

Those entities have subsequently been established by the Arizona

Department of Education.

Teacher Recruitment, Training and Retention

Research consistently shows that student achievement is greatly impacted by the quality of a student’s teacher.

28

Unfortunately, there are marked diculties with recruiting and retaining high-quality teachers in isolated rural areas,

which tend to contain underperforming schools and oer low rates of compensation.

29

These diculties greatly

impact Native students, as almost half of Native students attend schools in rural locations.

30

Several states have

enacted policies aimed at addressing these issues, which incorporate strategies for tuition assistance, specialized

credential programs and professional development.

CURIOUS ABOUT

COLLABORATION?

Below are a few documents intended to

guide collaborative eorts between state

and tribal leaders:

J National Conference of

State Legislatures: Models of

Cooperation Between States and

Tribes

J Tribal State Partnerships:

Cooperating to Improve Indian

Education

J Montana: Tribal Relations

Handbook—A Guide for State

Employees on Preserving the

State-Tribal Relationship

6

POLICY ANALYSIS

www.ecs.org | @EdCommission

Funding of Native Student Programs

Programs that specifically address the educational needs of Native students are generally funded

through one of three sources: BIE funding, the Indian Education Fund (IEF) and funds allocated by

individual states.

Bureau of Indian Education Funding

In fiscal year 2015-16, the BIE provided $553.5 million ($13,401 per student)

for the operation of tribal schools (those schools administered by tribes or by

the BIE).

43

In addition, the BIE provided $134.2 million ($3,251 per student) to

tribal schools for facilities maintenance and operations. These tribal schools are

also entitled to receive all of the federal funding allocated to traditional public

schools, including funding for low-income students (Title I), teacher/principle

training and recruitment (Title II) and special education (Individuals with

Disabilities Education Act).

Indian Education Fund

In fiscal year 2015-16, the U.S. Department of Education provided $143.9

million to educate Native students through IEF.

44

The IEF provides grants to

both traditional public schools and to tribal schools, with the grants averaging

approximately $300 per student. In fiscal year 2015-16 the U.S. Department of

Education also provided $33.4 million for Native Hawaiian students and $32.5

million for Alaskan Native students.

State Funding for Native Students

A 2013 study found that most states do not provide additional funding for either

tribal schools or for Native students attending traditional schools.

45

However,

Maine does provide additional funding for tribal schools in the state. Under

the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act of 1980, the state must provide tribal

schools with state funding above the amount of funding provided by the federal

government. Currently, the state has three K-8 tribal schools that receive state

funding. In addition, the state provides funding to students in ninth-12th grade

that can be used as voucher to attend the public high schools of their choice. In

the 2013 school year, the state’s three tribal schools received between $27,706-

$34,744 in total state funding per pupil. This compares to the state average

expenditure per student in fiscal year 2013 of more than $12,000.

46

7

POLICY ANALYSIS

www.ecs.org | @EdCommission

J South Dakota established a paraprofessional tuition assistance scholarship program, which will

be administered by the Oce of Indian Education. The 2016 bill creating the program supports

paraprofessionals employed by qualifying schools serving Native students as they pursue full teacher

certification.

31

J California requires the Commission on Teacher Credentialing to issue an American Indian language-culture

credential – with an American Indian language authorization, an American Indian culture authorization,

or both – to any teacher candidate who has met specified requirements.

32

The state authorizes credential

holders to teach in preschool, K-12 and adult education.

J In 2016, Utah created the American Indian and Alaskan Native State Plan Pilot Program, a five-year

initiative to provide grants to districts and charter schools to fund recruitment, retention and professional

development for teachers in schools with high concentrations of Native students.

33

Native Language Programs

While many factors impact student success, research suggests that culturally responsive schooling, including

indigenous language instruction, increases academic achievement of Native students.

34

Many states provide for

Native language education in their state laws, including funding immersion programs and language revitalization

grants.

J In 2015, Montana enacted legislation encouraging school districts to create Indian language immersion

programs. The bill also provided one-time funding to support districts.

35

J Oklahoma recognizes Native American languages as a language art, authorizes the teaching of Native

American languages in public schools, allows Native American language courses to count as fulfilling core

requirements, and allows qualified teachers to teach Native American languages.

36

J In 2012, Alaska established the Alaska Native Language Preservation Advisory Council to advise both the

governor and legislature on programs, policies and projects to provide for the cost-eective preservation,

restoration and revitalization of Alaska Native languages.

37

J In 2009, Wisconsin passed a bill permitting a school board or cooperative educational service agency, in

conjunction with a tribal education authority, to apply to the state department of education for a Tribal

Language Revitalization Grant. These grants are intended to support innovative, eective instruction in one

or more American Indian languages.

38

Culturally Relevant Curriculum

In addition to the practice of Native languages, culturally relevant curriculum that emphasizes the traditional

characteristics of each community has also been associated with Native student academic achievement.

39

Several

states require the incorporation of Native American history and other culturally relevant curriculum into their

lessons.

J Washington requires its public schools to teach the state’s tribal history, culture and government.

40

While

the state requires school districts to use curriculum developed by the oce of the superintendent of public

instruction, they are also authorized to modify the curriculum in order to incorporate elements that have a

regionally specific focus or to incorporate culturally relevant curriculum into existing materials.

8

POLICY ANALYSIS

www.ecs.org | @EdCommission

J New Mexico requires its Indian Education Division to develop or select culturally relevant curriculum for

Native students in kindergarten through sixth grade that specifically prepares them for pre-advanced

placement and advanced placement coursework in seventh-12th grade.

41

J Arizona requires that all schools incorporate Native American history into appropriate existing curricula and

that the curriculum includes the history of Native Americans in Arizona.

42

Policy Considerations

When determining the best way to positively impact Native students’ educational experiences, policymakers may

want to consider several opportunities for action, including:

Collaboration: Under ESSA, meaningful consultation with tribes must occur, and states can explore cooperative

agreements. States may decide to pursue the creation of an oce, commission or division dedicated to ensuring

that they meet the educational needs of Native students.

Funding: States may consider opportunities to provide additional funding to support schools with a high

concentration of Native students, whether public or tribal schools.

Teachers: State policymakers may consider focusing on the recruitment, training and retention of high-quality

teachers in schools with a high concentration of Native students. In doing so, states may want to consider programs

geared toward providing tuition assistance, specialized credentials and professional development opportunities.

Native Language: States may choose to implement native language immersion programs, ensure that schools oer

credits for native languages, or provide grant funding for language preservation and/or revitalization.

Curriculum: States may consider creating or incorporating curriculum that addresses the histories and cultures of

tribes in their state.

Additional Resources

J Bureau of Indian Education

J National Congress of American Indians

J National Indian Education Association

J The Native American Rights Fund

J National Caucus of Native American State Legislators

J Center for Native American Youth at the Aspen Institute

9

POLICY ANALYSIS

www.ecs.org | @EdCommission

Endnotes

1. National Caucus of Native American State Legislators, Striving to Achieve: Helping Native American Students Succeed (National

Conference of State Legislatures, 2008), https://www.ncsl.org/print/statetribe/strivingtoachieve.pdf (accessed August 2, 2016).

2. A note on Native Hawaiian students: Native Hawaiian students are sometimes included in discussions about education for Native

Youth. National statistics on the Native Hawaiian population are not consistently grouped with those of American Indian/Alaska Native

students. As such, we have chosen to limit our discussion in this paper to American Indian/Alaska Native students.

3. National Caucus of Native American State Legislators, Striving to Achieve: Helping Native American Students Succeed (National

Conference of State Legislatures, 2008), https://www.ncsl.org/print/statetribe/strivingtoachieve.pdf (accessed August 2, 2016).

4. Elementary and Secondary Education Act (as re-authorized by ESSA) 6 U.S.C. § 6151 (2016).

5. Bureau of Indian Education, 2016, http://www.bie.edu/index.htm (accessed July 30, 2016).

6. Ibid

7. Executive Oce of the President, 2014 Native Youth Report (December 2014) https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/

docs/20141129nativeyouthreport_final.pdf (accessed August 4, 2016).

8. “2011 National Indian Education Study: Summary of National Results,” National Center for Education Statistics http://nces.ed.gov/

nationsreportcard/nies/nies_2011/national_sum.aspx (accessed August 15, 2016).

9. “2011 National Indian Education Study: Regional and State Summary,” National Center for Education Statistics http://nces.ed.gov/

nationsreportcard/nies/nies_2011/national_sum.aspx (accessed August 17, 2016).

10. Ibid

11. Executive Oce of the President, 2014 Native Youth Report (December 2014) https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/

docs/20141129nativeyouthreport_final.pdf (accessed August 4, 2016).

12. The Education Trust, The State of Education for Native Student (August 2013) http://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/

NativeStudentBrief_0.pdf (accessed August 5, 2016).

13. “Public High School Four-Year on-Time Graduation Rates and Event Dropout Rates: School Years 2010-2011 and 2011-2012” National

Center for Education Statistics http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2014/2014391/findings.asp#f5 (accessed August 17, 2016).

14. Executive Oce of the President, 2014 Native Youth Report (December 2014) https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/

docs/20141129nativeyouthreport_final.pdf (accessed August 4, 2016).

15. Ibid

16. Elementary and Secondary Education Act (as re-authorized by ESSA) 6 U.S.C. § 6101 (2016).

17. Elementary and Secondary Education Act (as re-authorized by ESSA) 6 U.S.C. § 6101 (2016).

18. Bureau of Indian Education, “Restructuring the Bureau of Indian Education” 2016, http://bie.edu/cs/groups/xbie/documents/

document/idc1-031626.pdf (accessed August 14, 2016).

19. Bureau of Indian Education, “Restructuring the Bureau of Indian Education” 2016, http://bie.edu/cs/groups/xbie/documents/

document/idc1-031626.pdf (accessed August 14, 2016).

20. National Indian Education Association and Alliance for Excellent Education, Every Student Succeeds Act Primer: American

Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Students (Alliance for Excellent Education, June 2016) http://all4ed.org/wp-content/

uploads/2016/06/FINAL-ESSA_FactSheet_NIEA-American-Indian-Students.pdf (accessed August 3, 2016).

21. Ibid.

22. Every Student Succeeds Act, VIII (F)(II)Sec. 8538

23. Every Student Succeeds Act, VI (A)(2 &3) Secs. 6121, 6131

24. Helen S. Apthorp, Where American Indian students go to school: Enrollment in seven Central Region states (Regional Educational

Laboratory and Institute of Education Sciences, 2016) http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/central/pdf/REL_2016113.pdf (accessed

August 9, 2016).

25. Utah 53A-31-202

26. Washington RCW 28A.300.105

27. WestEd, Indian Education in Arizona, Nevada, and Utah: A Review of State and National Law, Board Rules and Policy Decisions

(WestEd, 2014) https://westcompcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/P6IndED_finalreport_WestEdcomm_cl_9.24.pdf

(accessed August 16, 2016).

28. “Teacher quality and student achievement: Research review,” Center for Public Education, 2005. http://www.centerforpubliceducation.

org/Main-Menu/Stangstudents/Teacher-quality-and-student-achievement-At-a-glance/Teacher-quality-and-student-achievement-

Research-review.html (accessed August 31, 2016).

© 2016 by the Education Commission of the States. All rights reserved. Education Commission of the States encourages its readers to

share our information with others. To request permission to reprint or excerpt some of our material, please contact us at 303.299.3609

or email [email protected]g.

Education Commission of the States | 700 Broadway Suite 810 Denver, CO 80203

10

POLICY ANALYSIS

29. Executive Oce of the President, 2014 Native Youth Report (December 2014) https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/

docs/20141129nativeyouthreport_final.pdf (accessed August 4, 2016).

30. “2011 National Indian Education Study: Summary of National Results,” National Center for Education Statistics http://nces.ed.gov/

nationsreportcard/nies/nies_2011/national_sum.aspx (accessed August 15, 2016).

31. South Dakota SB 81 (2016)

32. California AB 163 (2016)

33. Utah SB 14 (2016)

34. Angelina E. Castagno & Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy “Culturally Responsive Schooling for Indigenous Youth: A Review

of the Literature,” Review of Educational Research, vol. 78, no. 4 (2008): 941-993, http://www.mn-indianed.org/docs/

CulturallyResponsiveSchoolingForIndigenousYouth.pdf (accessed August 24, 2016).

35. Montana SB 272 (2015)

36. Oklahoma State Department of Education, Oklahoma Standards for World Languages (Oklahoma State Department of Education,

2015), http://sde.ok.gov/sde/sites/ok.gov.sde/files/2015%20World%20Languages%20Standards.pdf (accessed August 24, 2016).

37. “Alaska Native Language Preservation and Advisory Council” State of Alaska, https://www.commerce.alaska.gov/web/dcra/

AKNativeLanguagePreservationAdvisoryCouncil.aspx (accessed August 25, 2016).

38. “American Indian Languages in Wisconsin,” Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, http://dpi.wi.gov/amind/language-culture-

education/languages-wisconsin (accessed August 25, 2016).

39. William G. Demmert and John C. Towner “A Review of the Research Literature on the Influence of Culturally Based Education on the

Academic Performance of Native American Students,” Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory (2003) http://educationnorthwest.

org/sites/default/files/cbe.pdf (accessed August 15, 2016).

40. Washington SB 5433 (2015)

41. New Mexico 22-23A-5

42. Arizona ARS 15-710

43. “Budget Justifications and Performance Information Fiscal Year 2017: Indian Aairs” The United States Department of the Interior

(2016) https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/FY2017_IA_Budget_Justification.pdf (accessed September 21, 2016).

44. “Fiscal Year 2017 Budget Summary and Background Information” United States Department of Education ( 2016) http://www2.

ed.gov/about/overview/budget/budget17/summary/17summary.pdf (accessed September 21, 2016).

45. Lawrence Picus, et al, “An Independent Review of Maine’s Essential Programs and Services Funding”, Lawrence O. Picus & Associates.

April 1, 2013. (accessed September 16, 2016) http://www.maine.gov/legis/opla/EPSReviewPart1(PicusandAssoc%20)4-1-2013.pdf

46. United States Census Bureau

AUTHOR

Alyssa Rafa is a policy researcher in the K-12 institute at Education Commission of the States. She has her

master’s degree in international relations from the University of Denver. Outside of the oce, you can find

Alyssa enjoying the great outdoors with her new husband, Mickey.

Special thanks to Mike Grith for his contribution to the funding section of this paper.