Advertising in the periphery: Languages and schools

in a North Indian city

CHAISE LADOUSA

Department of Anthropology

Miami University

Oxford, OH 45056-1879

ABSTRACT

Written school advertising in Banaras, a North Indian city, creates corre-

spondences between a language activity and central and peripheral places.

In spoken discourse, complex relationships inhere between ways of describ-

ing languages as varieties and the sociological value that is said to exist in

the fit between a language variety and its domain of use. Education is one

such domain because the educational system itself is organized in popular

discourse by medium, Hindi or English. In spoken discourse, Hindi- or

English-medium schools can indicate central or peripheral dispositions. Ad-

vertising, however, includes a meaningful element unavailable to speakers

in the flow of interaction – a distinction between lexical designation and its

rendering in Devanagari or roman script. Therein lies its power to establish

English as central and Hindi as peripheral. (Language politics, genre, lan-

guage community, advertising, North India.)*

While conducting fieldwork in Banaras, a city of approximately two million in

North India, I decided to take the fourteen-hour train trip to Delhi, the national

capital. There, I met with a retired official of one of the many school accreditation

boards in India. We talked about schooling and language. I explained that most of

the Banaras residents, students, teachers, and even school principals with whom

I had been working were not aware of many of the topics she had mentioned. The

retired official was not surprised, and she replied quite simply, “Education out-

side of Delhi is a disaster.” Her statement constructed Delhi as a center, a place of

order where the activities and aims of educational bureaucracies are known to its

inhabitants; people who reside outside, in the periphery, are ignorant. On the

return trip, I met a couple of middle-class appearance traveling from Delhi to

Banaras to visit relatives. As the train slowed on its entry into Banaras, the man

lifted the aluminum shade shielding us from the sun. His wife, glancing out of the

window as she readied their things to disembark, exclaimed in Hindi, ‘We have

reached hell’ (narak pahu˜c gaye hãı˜). The clever woman enacted an arrival sce-

nario whose ironic twist relied for its effect on Banaras’s place in the periphery.

She toyed with potential meanings of hell (narak), one contradicting Banaras’s

Language in Society 31, 213–242. Printed in the United States of America

DOI: 10.1017.S0047404501020164

© 2002 Cambridge University Press 0047-4045002 $9.50

213

pan-Indian reputation as a Hindu holy site, and the other constructing the scene in

front of her as unpleasant, and, as she told me moments later, ‘dirty’ (ganda¯ ).

The train provides a conduit from the periphery to the center and back again.

Although specific descriptions and constructions vary, the difference created by

distinctions between a center and its periphery is often salient in conversations

across North India. Interchanges like those described above intersect and reenact

notions expressed in other places and times. A fairly common rendition, for ex-

ample, is that Delhi, the center, is orderly and provides bureaucratic and com-

mercial employment opportunity for migrants, but also heightened risk. In contrast,

places outside Delhi are disordered, isolated, and economically stagnant, but also

relatively safe on account of their well-entrenched notions about class and the

potential for mobility.

Constructions of center and periphery in North India are not always played out

in such discrete and neat juxtapositions of place. This article investigates the

ways that Hindi and English can be used to construct center0periphery distinc-

tions in talk about schools located within Banaras. Before I consider how lan-

guage distinctions are used to create centers and peripheries, however, it is

necessary to understand that they embody another relation, that between the local

and the global. People in Banaras identify local schools and local people associ-

ated with them as Hindi- or English- “medium,” according to the language in

which most school subjects are taught. The designation of practices as “Hindi”

indexes (Silverstein 1976) them as local and indigenous, and “English” indexes

them as Delhi-like and foreign; “medium” transposes these qualities onto schools

and those who attend them or are in their employ. Language medium distinctions

constitute what Urciuoli calls a language “border”: “Borders are places where

commonality ends abruptly; border-making language elements stand for and per-

formatively bring into being such places” (1995:539). Mention of a school’s me-

dium launches the school into an oppositional contest configured by a language

border dividing local Hindi from global English. Silverstein notes that any con-

struction of locality is relational: “‘Local’ language communities do not exist in

a state of nature; the very concept of locality as opposed to globality presupposes

a contrastive consciousness of self–other placement that is part of a cultural project

of groupness” (1998:405). Discourse about medium in Banaras indexes the local

in contrast to the global, but institutional examples of the global – English-

medium schools – can be found locally.

One of the most fascinating aspects of spoken discourse about medium is that

speakers’ transformations of the relationship between the local (Hindi) and the

global (English) into distinctions between a center and its periphery are not al-

ways predictable. Explored in this article are the ways that a speaker might praise

Hindi-medium schools as patriotic and indicative of the nation (center), and dis-

parage English-medium schools as not just foreign but unpatriotic (periphery).

Another might disparage Hindi-medium schools as tied to an isolated Hindi re-

gion (periphery), and English-medium schools as offering a language of pan-

CHAISE LADOUSA

214 Language in Society 31:2 (2002)

Indian or international value (center). The value of attending one or the other

medium is constructed relationally, but it is variable within shifts of what is cen-

tral and what is peripheral.

Gupta & Ferguson ask, “How are understandings of locality, community, and

region formed and lived?” (1997:6).Answers may depend significantly on the par-

ticular sphere of language activity about which the question is asked. School ad-

vertising in Banaras is another domain of language activity involving educational

institutions. My parallel consideration of spoken discourse and written advertis-

ing demonstrates that constructions of center and periphery are not always vari-

able in language activity in Banaras that involves schools. Spoken discourse and

written advertising offer different possibilities for the construction of the central

and peripheral, and the difference depends crucially on the semiotic tools pro-

vided by each domain of linguistic activity. In sum, advertising for schools presents

a domain of linguistic activity in which “structures of reception and evaluation”

differ significantly from those in spoken discourse (Spitulnik 1993:297). Adver-

tising includes written language and provides distinctions between scripts, not just

languages, as indexes in linguistic constructions of central and peripheral spaces.

I present examples of school advertisements below in order to demonstrate that dif-

ferent combinations of languages and scripts are indexical in a realm of linguistic

activity in which center0periphery relations between Delhi and Banaras are quite

certain and, relative to spoken discourse, inflexible.

LOCAL AND GLOBAL IN SPOKEN DISCOURSE ABOUT LANGUAGE

MEDIUM

The very mention of schools in North India often invokes a contest in value.

1

Hindi and English are opposites and competitors, and the mention of a school

often invites its demarcation as Hindi- or English-medium and its comparison

with the other type. In order to understand the capacity of language distinctions to

denote schools in this bipartite, competitive structure, it is necessary to under-

stand that talk about schools necessarily excludes many other languages spoken

in Banaras – even some that are taught in schools. Concomitantly, the opposition

of Hindi and English that medium entails radically transforms the value of Hindi

in other domains beyond its indexing a school as Hindi-medium. In its dual man-

ifestation as Hindi or English, medium effects a self-contained construction of

the local and the global, respectively.

India’s sociolinguistic scene has been perceived as unique because of its rel-

atively stable plurilingualism over social and geographic space and within indi-

viduals (Aggarwal 1997). In sociolinguistic work in North India, one of the most

salient distinctions is between a standard and its plural, more localized varieties.

Banaras is typical of North Indian locales in that it lies in the region of a recog-

nized standard – Hindi – and in the domain of a more limited regional variety,

Bhojpurı¯. Gumperz (see Gumperz 1958, 1961, 1964, 1969; Gumperz & Das Gupta

ADVERTISING IN THE PERIPHERY

Language in Society 31:2 (2002) 215

1971; Gumperz & Naim 1971) has provided the most sophisticated sociolinguis-

tic description of the North Indian Hindi-speaking region in a three-tier model.

First, a more or less unified morphological, phonological, and syntactic system

exists as a standard. It is utilized in many literate contexts and can be associated

with vocabulary derived from Persian and Arabic vocabulary that cues its man-

ifestation as (Muslim) Urdu, or with a Sanskrit-derived vocabulary in its mani-

festation as (Hindu) Hindi.

2

Although much disagreement exists on the point,

neither association is a necessary feature of the standard’s use in conversation.

Therefore, I will call it “Hindi.” The language defines a vast region of North India

as the “Hindi Belt,” a set of states that share Hindi as an official language. Sec-

ond, Gumperz defines the Hindi area as comprised of a set of regional varieties.

Within the Hindi Belt, Banaras lies in the Bhojpurı¯ language region. Some schol-

ars have deemed Bhojpurı¯ more language-like and some more dialect-like,

3

but

whatever its designation, Bhojpurı¯ is spoken in a much smaller area than is Stan-

dard Hindi and itself contains several demarcations of consistent variation (Gri-

erson 1927).

4

Gumperz’s (1958) third level of linguistic variation is the village,

and Banaras, lacking the distribution of castes by area on which this third level is

based, perhaps manifests a different sort of variation. Nita Kumar 1988 describes

the salience of neighborhood designations in Banaras, and many people associ-

ated linguistic distinctions with neighborhoods when describing these to me.

The pre-college school is an institution that creates particularly strict and sa-

lient demarcations in social space between these levels of linguistic variation.

Already present in Gumperz’s description of linguistic plurality is the idea that

languages in North India are not distributed evenly over social spaces (K. Kumar

1991, 1997). Descending tiers in Gumperz’s model reflect decreasing geograph-

ical spaces and decreasing presence in institutions, official contexts, and publish-

ing venues. Among language varieties, however, only the state-recognized standard

language is appropriate for use within schools.

5

The “three language formula” is

the name of the Indian government’s policy on what languages students should

study in schools. The three languages include “their [students’] own regional

language [in Banaras, Hindi], a foreign language (almost always English), and

either Hindi in the non-Hindi-speaking areas or a language other than Hindi in the

Hindi-speaking areas” (Brass 1990:143). This formula provides a particularly

clear articulation of how linguistic varieties in Banaras reflect demarcations of

social space. Nowhere in the formula is there the provision for instruction in

Bhojpurı¯. Without exception, when I asked people in Banaras whether Bhojpurı¯

should be taught in school, my question was met with laughter, and sometimes

open derision. To my further queries, people offered that Bhojpurı¯ is a ‘language

of the home’ (ghar kı¯ bha¯

.

sa¯ )ora‘language of the village’ (g

I

a¯ vkı¯ bha¯

.

sa¯ ) – in

other words, too local to be used in school.

While the formula excludes Bhojpurı¯ from the school, it constructs the school

as a place where Hindi as well as other languages are necessarily found. The

official rationale for including three languages in pedagogy is that it combats the

CHAISE LADOUSA

216 Language in Society 31:2 (2002)

isolationist promotion of state languages only. India is a nation comprised of

many linguistically demarcated states; the formula provides knowledge of lan-

guages that transcend state-based linguistic differences. Hindi receives special

mention in the formula because many in the central government hoped that Hindi

would become a national language. Universal competence in Hindi, according to

its proponents, would bridge the mutual unintelligibility between state-recognized

standards. That Hindi was already the state-recognized standard of a large and

powerful block of states in North India, the Hindi Belt, was not lost on other

states, however. The formula has increasingly represented a compromise in na-

tional language politics because the specific languages required were adjusted in

the wake of region-based resistance to the pan-Indian privileging of Hindi (Das

Gupta 1970, Brass 1974). Resistance to Hindi was especially fierce, and some-

times even violent, in the South; Tamil opposition to pan-Indian adoption of

Hindi was particularly effective (Ramaswamy 1997). Brass explains that, in its

enactment, the three language formula has largely failed “for lack of genuine

desire to implement it in most states, lack of teachers competent in the various

languages willing to move outside their home states, and the recognition in North

India of Sanskrit, Urdu, and the regional languages and dialects of the north as

alternative third languages in the formula rather than languages of the non-Hindi-

speaking regions” (1990:143). The formula, however, continues to inform what

languages a school-going child should master.

The notion that schools are sites where plural languages are offered to inte-

grate students into the national linguistic realm is largely lost on Banaras resi-

dents. They are not nearly so concerned with the languages offered in schools as

they are with the demarcation of schools by means of language distinctions. Those

with whom I worked in Banaras find the language “medium”–Hindi or English –

in which subjects are taught to be a highly charged, compelling aspect of a school’s

identity. Many types of schools exist in Banaras whose mention does not require

language distinctions: those that are supported by the government, those that take

fees, Montessori schools, convent schools, voluntary schools, or those based in

religious affiliation. There are also many boards which set syllabus requirements

and testing and whose identification does not require language distinctions. One,

the Uttar Pradesh (UP) Board, is administered by the government of Uttar Pradesh,

the state in which Banaras is located. Others are administered by institutions that

largely exist outside the state; private, fees-taking schools are associated with

these.

Medium, however, organizes many of the aforementioned types of schools

and boards into a dichotomous realm of contestation. The medium of a school is

so important because it resonates with practices in domains outside and beyond

the school. Bourdieu 1977, 1992 has argued that when the value of linguistic

practices arises across domains of use, a “market” for that language exists. Schools

provide conduits to language markets in which students will bring to bear lin-

guistic capital provided by their school experiences. The designation of a partic-

ADVERTISING IN THE PERIPHERY

Language in Society 31:2 (2002) 217

ular school’s medium – Hindi or English – opposes it to members of the other set;

the medium of a school indexes the school’s position within a dichotomous set of

associations that point to discrete markets. Hindi-medium schools are largely

associated with the government, with the nation, with a lack of cost, and, in a

metonymic transposition to be discussed below, with the Uttar Pradesh Board. In

contrast, English-medium schools are associated with the families who own them,

with places outside the Hindi Belt or the Indian nation, with high cost, and with

boards not administered by the state of Uttar Pradesh.

This dual configuration of language markets and its realization in medium

distinctions is made possible by schooling’s transformation of the ways that lan-

guage distinctions interact with the local and global outside literate or institu-

tional contexts. Outside such contexts, as in Gumperz’s three-tier description,

Bhojpurı¯ is the language of the region, the house, and the local; inside such con-

texts, Bhojpurı¯ is excluded, and Hindi assumes the value of the local. The three

language formula’s construction of the global – the idea that a language other

than Hindi might enable communication with places outside the Hindi region – is

preserved in language-based demarcations of school types, and it is embodied in

English. Thus, Hindi is local, but only in contrast to global English.

Perhaps the clearest configuration of English as global and Hindi as local was

born out of statements by students, parents, principals, and even persons not

involved with schools that, in order to ‘go outside’ (ba¯har ja¯na¯ )orto‘roam’

(ghumna¯ ), control of English is a valuable asset. Some asserted that to go else-

where, ‘English is necessary’ (ãgrezı¯ zarurı¯ hai ). People associated with either

Hindi- or English-medium schools explained that English (and not Hindi) is a

ticket for departure. Departing Banaras requires English and offers greater access

to employment. Whether for leisure or work, travel outside Banaras is one goal of

those attending English-medium schools. Indeed, many people explained to me

that English-medium education makes one like Delhi residents whose English is

uncluttered with Hindi. Travel, jobs, and linguistic competence converge in

English-medium schools in Banaras because those particular schools are indic-

ative of life in other places.

CENTRAL AND PERIPHERAL IN SPOKEN DISCOURSE

AND ADVERTISING

Hindi- and English-medium’s ability to index the local and the global does not

exhaust medium’s potential to construct social space. Local Hindi and global

English can be configured within another set of relations: the central and the

peripheral. What is possible in such configurations, however, depends crucially

on the sphere of communication in which they take shape. In the heat of discus-

sion, parents, students, and teachers have two configurations open to them: In

one, English embodies the center and Hindi the periphery; in the other, Hindi

embodies the center and English the periphery. Advertising for schools, in con-

CHAISE LADOUSA

218 Language in Society 31:2 (2002)

trast, offers but one configuration: central English and peripheral Hindi. In the

rest of this article I investigate the reasons that spoken discourse and advertising

provide different possibilities for the construction of Hindi- and English-medium

schools as central or peripheral. I argue that advertising, relative to spoken dis-

course, presents indexical relationships that are less creative in constructing Hindi-

and English-medium schools as central and peripheral.

One configuration of the two types of schools in spoken discourse as indexical

of a center and periphery has already been noted. English-medium schools pro-

vide a route out of Banaras because they offer access to jobs elsewhere, particu-

larly in Delhi. Initially confusing to me was the fact that children of parents

engaged in the lowest-paid occupations figured frequently in descriptions of

English-medium student bodies, but not in those of Hindi-medium schools. Upon

further questioning, people included increased access to jobs as a rationale for

attendance by the poor. Mohan reflects on English’s centrality succinctly: “The

Indian student . . . is a disadvantaged individual seeking a secure niche at the top

of a shortages-economy in a ruling group largely defined by its mastery of En-

glish” (1986:16). In contrast, Hindi-medium schools do not provide access to a

center defined, in Banaras, by increased employment opportunities elsewhere.

Some people claim that attendance at Hindi-medium schools makes movement

outside impossible and therefore denies outside employment opportunities. Other

people, associated specifically with Hindi-medium schools, offered that attend-

ing Hindi-medium schools indicates ‘satisfaction’ (santu

.

s

.

t) specifically because

the desire to go elsewhere is missing. Satisfaction established Hindi-medium

schools as an alternative to the desire for relocation’s economic possibilities and

indicated a laudable willingness of Hindi-medium students to remain in the pe-

riphery. Many of these same people scoffed at the efforts of the poor to gain

economic benefit from English-medium schools. They explained that without

necessary connections, the poor would not be able to get jobs.

Increased employment opportunities did not comprise the only construction

of language and education in terms of a center and its periphery. Another possi-

bility exists in spoken discourse that sets Hindi firmly in the center and English in

the periphery.

6

Fox 1990 has noted the rise of the “Hindian,” an identity based on

the construction of India and its inhabitants as essentially Hindu. One of the

primary ways that Hindu fundamentalist organizations have equated India with

Hinduism is by juxtaposing both to English; they describe English as the lan-

guage of colonialism and foreigners. Hindi, deriving lexical items from Sanskrit

(and not Urdu), has become the language of the “Hindian” and has served to

differentiate the loyal from the foreign. This construction of the nation in terms of

opposition to the foreign, while rooted in notions of an essential Hindu identity,

has extended the imagination of Indian identity beyond Hinduism per se.

In Banaras, many Hindi-medium school-goers explicitly indexed patriotism

and national loyalty with their mention of Hindi as well as their attendance at

Hindi-medium schools.

7

Only once in a year of fieldwork did I hear nationalism

ADVERTISING IN THE PERIPHERY

Language in Society 31:2 (2002) 219

indexed through Hindi’s ties to religion. I decided to visit a Hindi-medium school

run by the Hindu nationalist group, the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh).

8

Throughout our lengthy conversation, the principal provided Sanskrit-derived

alternatives for many of the words I used. He explained very politely that I had

learned much Urdu inAmerica, and that I should endeavor to learn ‘pure’(shuddh)

Hindi. Sanskrit-derived terms provided the principal a Hindu corrective to my

problematic alien language. Much more commonly, however, Hindi-medium

school-goers and their families explained that Hindi is India’s ‘national lan-

guage’ (ra¯

.

s

.

trabha¯

.

sa¯ ). In discourse that equates Hindi with the nation, Banaras as

a whole occupies a place of centrality by virtue of its place within the Hindi Belt.

9

Many of these same people explained that English is an ‘international language’

(antarra¯

.

s

.

trabha¯

.

sa¯ ). English-medium students explained Hindi’s status similarly,

but they never ventured toward Hindi-medium students’ claims that English is

‘foreign’ (videshı¯). Hindi is an index of the Indian nation, but for Hindi-medium

school-goers, its opposition to English indexes inclusion, a center. Thus, many

Hindi-medium students described English-medium students to be ‘not Indian’

(bha¯ ratı¯ya nahı˜).

Advertising for schools presents a sphere of linguistic activity in which dom-

inance and subversion are not nearly so malleable as in spoken discourse about

schooling. Hanks, drawing on Bakhtin’s (1986) writings on genre, notes that

“conventional discourse genres are part of the linguistic habitus that native actors

bring to speech, but that such genres are also produced in speech under various

local circumstances” (1987:687). School advertising and everyday conversations

about schools comprise different genres in part because they provide different

means of constructing relationships between languages and institutions. The very

possibilities of the construction of value within the two linguistic markets of

Hindi- and English-medium thus vary according to whether the construction oc-

curs within spoken discourse or in advertising. Markets are accessed by certain

modes of linguistic activity whose semiotic properties seem, potentially at least,

to make all the difference in what may be dominant and what may be contested.

10

In order to understand advertising’s comparatively limited indexical possibil-

ities, it is necessary to understand that certain semiotic properties extant in ad-

vertising for schools are not available to speakers in spoken discourse. Nowhere

in advertising (as is quite common in spoken discourse) is the relationship be-

tween language variety and its appropriate use raised to the level of ostensive

reference – for example, “English is the language of some in Delhi.” Written

language makes available a kind of semiotic relationship unavailable in everyday

conversation; both Hindi and English lexical items can be represented ortho-

graphically in Devanagari

11

or roman script. This mixing is of a kind impossible

to represent with the spoken word; speech can only describe the relationship

between lexical affiliation and its scripted representation.

Advertising presents two realms of indexical activity: advertisements found

around town, and advertisements found in newspapers that reach Banaras from

CHAISE LADOUSA

220 Language in Society 31:2 (2002)

Delhi or Lucknow, the state capital. School advertisements found around Banaras

contain all possible combinations of Hindi and English lexical items with De-

vanagari or roman script. School advertisements that reach Banaras via news-

papers, in contrast, lack such variability in combinations of lexical item and script;

only one combination of lexical affiliation (English) and script (roman) is present

in school advertisements in newspapers. The sum total of lexical and script com-

binations in school advertisements in the newspaper thus corresponds to only one

of the possible combinations in Banaras – the combination, we will discover

below, that indexes the most expensive schools. Newspaper advertising thus ren-

ders the plurality of indexical possibilities in advertising found off the printed

page – around town in Banaras – itself an index (Silverstein 1996).

The lack of indexical play in school advertisements in the newspaper renders

other combinations of lexical item and script, prevalent around town, indexes of

Banaras’s peripheral status. Advertisements for schools in newspapers arriving

from elsewhere are indexes of the center as a result of their paucity of lexical0

script combinations. Banaras’s bid for centrality, in which the Hindi-medium

school indexes the Indian nation, is subsumed in local advertising as but one

participant in Banaras’s apparent diversity, and it is altogether missing in adver-

tisements in newspapers coming from the center. Banaras as a whole, from the

perspective of indexical possibilities present in the newspaper, is a peripheral

place where deviation exists.

ADVERTISING SCHOOLS

All combinations of lexical affiliation (Hindi or English) and writing system

(Devanagari or roman) can be found virtually anywhere in urban centers in

India, where advertisements clog the public visual field. Advertisements cre-

ated by schools, however, form a special group vis-à-vis other advertisements.

Among school advertisements, the relationship between lexical item and script

is a meaningful sign. This differs from advertisements generally, where lexical

items and scripts are not necessarily coordinated. School advertising differs

from other types of advertising because it presents predictable combinations of

lexical element and script, depending on what school or board is being adver-

tised. The combinations in advertisements for schools and tutorial services in

Banaras presented below are indexical because English lexical items rendered

in roman script and Hindi lexical items rendered in Devanagari script are present

in advertisements that represent the most expensive English-medium schools

and the most government-associated Hindi-medium schools, respectively.

Deviations (other combinations of lexical item and script) are quite prevalent

in Banaras, but they are always subject to the charge of being “muddled.” Parents,

teachers, and principals associated with both mediums were unconcerned about

combinations of lexical item and script in commercial domains exclusive of ed-

ucation. Advertising by educational institutions, however, was a different matter.

ADVERTISING IN THE PERIPHERY

Language in Society 31:2 (2002) 221

Larger ideologies about the necessity of standard language for participation and

success in school intersected with evaluations of lexical0script combinations in

school advertising. Teachers and parents consistently identified spelling and gram-

mar as two of the hardest things for students to master. Each of these practices

presupposes a standard written in a standard orthography. Notions of standard

drew the line between inconsequential lexical0 script combinations in advertising

for commercial products, and lexical0script combinations in advertising for ed-

ucational institutions in which pedagogical effects inhere. Thus, while the deno-

tation of the particular school is handled by the school’s name, the combination of

lexical affiliation and script embody a separate sign function that indexes the

social value of the school. The efficacy of this indexical sign function presup-

poses that it is indeed an educational institution that is being advertised.

In Banaras, as elsewhere in urban North India, it seems that one is never out of

sight of an advertisement for a school. There are cloth, paper, plastic, or metal

signs hung over the street or affixed to walls; there are huge billboards set behind

and high above the walls lining streets; metal or wooden signs nailed high on

telephone, electric, or other kinds of poles advertise schools. Perhaps most com-

monly, signs are painted directly onto walls lining the streets. I remember reading

daily, while getting a pa¯n (a betel nut and leaf packet with spices that is chewed)

at the nearest crossing, a sign, long faded, advertising a local school. It had been

painted directly onto the neighboring pa¯n stall before the one I patronized was

built, obscuring the advertisement from all but customers who had visual access

to the one-foot space between.

In Banaras, advertising creates a stark contrast between government-

administered schools and private schools. Most schools have a sign near the

entrance gate, and government-administered schools are no exception, but this

is the extent of government-administered schools’ advertising. Private schools

of both mediums, in contrast, advertise vigorously. Besides the sign at the en-

trance, private schools have signs placed all over the city’s public spaces, so

that they are among the most advertised items in town. Both Hindi-medium

and English-medium private schools advertise, but in very different ways. An

obvious difference was in the script used, and less variably, in the language in

which the advertisement appeared. One might predict, as I did initially, that

English-medium schools advertise in English, using roman letters, and that Hindi-

medium schools advertise in Hindi, using Devanagari letters, but this was not

always, or even mostly, the case. My initial predictions did hold in the case of

the convent school on the outskirts of the city and the fees-taking English-

medium branches of one of the most expensive schools in Banaras, the Sea-

crest School, in which I conducted fieldwork. Their signage always looked the

most expensive to produce, and their advertisements were the only ones to

reach the domain of television. Among these schools, issues of language and

its representation in script were moot, for no Hindi or Devanagari appeared.

CHAISE LADOUSA

222 Language in Society 31:2 (2002)

Other schools’ advertisements were somewhat less predictable in terms of a

match between the language medium of pedagogy and that of advertising. Some

schools left the medium of pedagogy completely unmentioned. Their names might

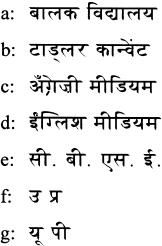

utilize Hindi words – ba¯lak vidya¯laya ‘child school’(for original, see Fig. 1a), for

example – or English words, such as “Toddler Convent.” Sometimes the English

words appeared in Devanagari renditions – ta¯

.

dlar ka¯nvent (Fig. 1b); sometimes,

though seldom, the Hindi titles appeared in roman renditions, such as, “Baalak

Vidyalay” (‘child school’). Among these schools, there was no easy way to guess,

unless it was explicitly stated, what medium was being advertised. The sign in

front of government schools, in contrast, was always in Devanagari, and in the

few “Central Schools,” regarded as the most prestigious of the government schools,

the English name, “X Central School,” was followed by its representation in

Devanagari.

Rarely did schools advertise that they were Hindi-medium. Advertisements

for hundreds of schools included only one or two examples of schools that put

“Hindi-medium” on their sign or in their roadside advertisements.

12

Self-

proclaimed English-medium status was much more common and many fees-

taking schools stated explicitly in their advertisements that they were English-

medium. Most often this was advertised in roman letters, though sometimes

the lexical items were rendered in the Devanagari equivalent: angrezı¯ mı¯diyam

‘English-medium’ (Fig. 1c), angrezı¯ being Hindi for ‘English’,orı¯nglis´ mı¯d-

iyam ‘English-medium’ (Fig. 1d), a direct transliteration. Not until the end of

my stay did it strike me how ridiculous it would be to see “Hindi-medium”

(English lexical items in roman script).

Some schools also advertised their board affiliation. The Uttar Pradesh Board,

commonly called the “UP Board” in conversation, is located in Allahabad, Ba-

naras’s closest urban neighbor. It oversees many schools that are government-

figure 1: Devanagari-rendered items that appear in the text.

ADVERTISING IN THE PERIPHERY

Language in Society 31:2 (2002) 223

funded and administered. Much more commonly advertised, however, was a

school’s affiliation with the Central Board of Secondary Education, centered in

Delhi. The acronym usually sufficed, whether in conversation or advertisement;

in advertising, one would see “C. B. S. E.” (Central Board of Secondary Educa-

tion), or the Devanagari letters referring to the English letters of the acronym –

see Fig. 1e (sı¯.bı¯. es. ı¯.). Consistently, CBSE affiliation is claimed by the most

expensive schools in town. In turn, the CBSE is juxtaposed to the UP Board in

conversation. The two boards stand in opposition, parallel to the relationship

between English– and Hindi–medium schools. Whereas UP Board affiliation is

rarely advertised, claims of CBSE affiliation are often the subject of comment

and dispute. People targeted precisely these schools when they made accusations

that English-medium, fees-taking schools’ claims of board affiliation were false.

These combinatorial possibilities are presented to demonstrate how advertis-

ing illustrates a difference in schooling through language use in visually repre-

sented form. Though types of advertising are many, most advertising forms utilized

by schools in Banaras include only written words in representing their commod-

ities. Two exceptions are the photographs of particularly successful students that

figure 2: The range of language representations in school advertising in Ba-

naras: combinations of language and script.

CHAISE LADOUSA

224 Language in Society 31:2 (2002)

appear in the advertisements for tutorial services, and the school crest, which

sometimes appears within a school’s advertisement. Some expensive English-

medium schools (the Seacrest School, for example) have begun to air television

advertisements on local cable, but they are the only type of school to have done

so.

13

Most commonly, school advertising uses only written language as its rep-

resentational form.

The correspondence between school medium and linguistic medium of ad-

vertising was not universal; however, two of the schools I focused on during

fieldwork – a government-administered, Hindi-medium school that I will call

the Saraswati School, and the fees-taking, English-medium Seacrest School –

represent end-points in the spectrum of what happens linguistically in the pub-

lic representation of schools through advertising. For these two schools, the

relationship between school type and characteristics of advertising (language

medium, language used in advertisement, script used in advertisement, board

affiliation) was predictable. For other schools, these variables intermixed sig-

nificantly, and some used the “inconsistencies” to build a commentary on the

school’s legitimacy.

Considered together, lexical choice between Hindi and English and the script

in which either is written illustrate particularly clearly the way that advertising

constructs an index of language medium. In other words, lexical0script combi-

nations index the particular institution represented by the advertisement as be-

longing to a type. Two consequences result from a lexical0script combination’s

indexical function. First, the indexical nature of lexical0script combinations in

advertisements for schools disregards linguistic complexity within the institu-

tions indexed. The realm of advertising does not have to account for the more

complex linguistic interactions that actually take place in all types of schools –

for example, the linguistic maneuvering in Hindi and English that goes on in the

Seacrest School’s principal’s office when parents bring their children for the en-

trance examination, or a rather complex discussion between a veteran govern-

ment school teacher and myself of the changing ways that Hindi and English have

been used in government school teaching. School and tutorial service advertise-

ments thus seem like particularly total examples of what Gal & Irvine have la-

beled “semiotic erasure”: “the process in which ideology, in simplifying the field

of linguistic practices, renders some persons or activities or sociolinguistic phe-

nomena invisible” (1995:974). The end-points of advertising’s combinatorial pos-

sibilities of lexical and script choice erase the semiotic possibilities of the use of

both languages in such conversations; consequently, advertising exists as a some-

what self-contained system of school differentiation. This is possible because

advertisements for schools rely for meaning construction on differences that are

not necessarily salient in advertising for other products. This is the second con-

sequence of the indexical force of lexical0script combinations, and it illustrates

why the indexical nature of medium distinctions in written advertising differs

from that in spoken discourse. The two types of schools that stand as end-points

ADVERTISING IN THE PERIPHERY

Language in Society 31:2 (2002) 225

in the spectrum of possible combinations of languages and scripts do so precisely

because, in their cases, those combinations are predictable within the larger lin-

guistic scope of advertising, school-based or not.

The cases of other schools, where combinations are more variable and “mud-

dled,” correspond to what one might call “non-elite” sites of literacy in North

India. These sites are characterized by a lack of internal systematicity between

representation and language on the one hand, and language and script on the other

(see Fig. 2). One might find examples in advertisements for products such as

soap, matches, or even automobiles that are ubiquitous in North India. In these

arenas, it is possible that elements of a product’s linguistic representation might

draw comments about the correspondence between language and the product’s

symbolic consumption. There is nothing predictable, however, in representa-

tional choices between English and Hindi lexical items, and roman or Devanagari

script.

figure 3: Relationship of script and language in school (and board) advertising,

with predictable cases specified.

CHAISE LADOUSA

226 Language in Society 31:2 (2002)

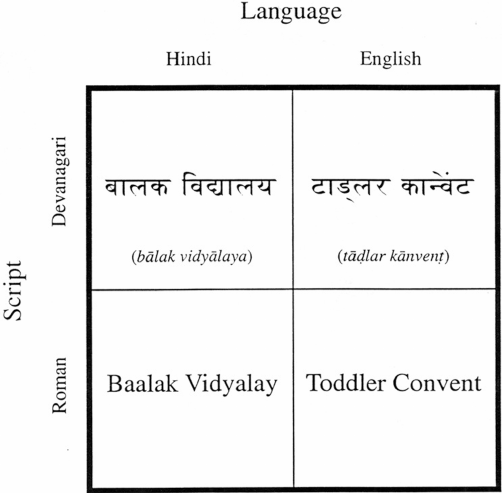

Fig. 4 shows the name of the store, prominently painted in Devanagari over the

entrance: barman s

.

tors, named after its owner. Just outside the store proper are

many accouterments of daily life: water buckets and plastic cricket bats, and just

inside the entrance, hanging from the ceiling, baby dolls and toy animals. Inside,

one can find all the manner of general goods, from paper to underwear. The

photograph was taken in the hot season and an air cooler sits on the end of the

counter for the clerk’s comfort – a comparative luxury, complementing the ceil-

ing fan found in most stores like this, but not in smaller stalls where more limited

selections of household goods can be found. Painted with the store’s name above

the entrance is a symbol for a soft drink company and the address and phone

number of the store. There is all manner of advertising, from a popular battery

manufacturer (entirely in English) to a sign in the upper right-hand corner of the

door frame for saral kocing (‘easy coaching’), an advertisement for a local Hindi-

medium tutorial service. ‘Coaching’ is borrowed from English, but it is a com-

mon term for tutoring across North India.

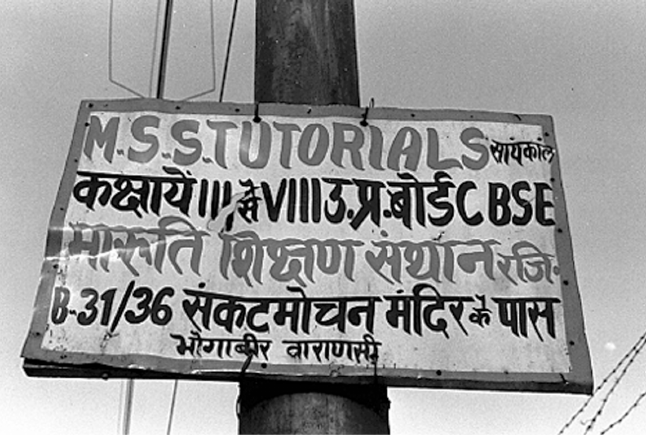

Fig. 4 shows a general store, while Fig. 5 shows the larger group of stores in

which it is situated. Barman Stores is the next store on the left, out of the picture.

From left to right, there is a dry-cleaner, another general store, a pharmacy, and a

laundry service. Advertising abounds; logos and lexical items utilize Hindi and

figure 4: Mr. Barman’s shop.

ADVERTISING IN THE PERIPHERY

Language in Society 31:2 (2002) 227

English, and use Devanagari or roman script as means of representating both.

Fig. 5 illustrates all possible combinations. s´ri na¯th janaral s

.

tors (Shri Nath Gen-

eral Stores) is painted in Devanagari just above the entrance to the store, just as in

the case of Mr. Barman’s shop, and written again, but in roman script, “SHRI

NATH GENERAL STORES.” This roman-script rendition is included on a plas-

tic signboard for a soft drink whose consumption many associate with activities

foreign or attributable to ‘big people’ (ba

.

re log). (However, another sign for the

same soft drink company, not more than a mile away, utilized Devanagari script

to convey its English lexical items, janaral s

.

tors.) Just underneath is a cigarette

advertisement, brand name in English

14

(roman script) and accompanying slogan

in Hindi (Devanagari script). Painted on the head of the bench in front of the row

of stores is yah

I

a¯ par vi

.

diyo gem kira¯ye par diya¯ ja¯ ta¯ hai (‘video games are rented

here’), all rendered in Devanagari. As in the case of soft drinks, many people

claimed that videos and video games are something foreign; nevertheless, they sit

comfortably in an entirely Hindi sentence.

15

Advertising is susceptible to multiple interpretations and can trigger multiple

commentaries or criticisms. What is possible depends on the historical circum-

stances of the viewer’s life, current contextual factors, and the imagination of

those engaged, but advertising done in the domain of schooling is less open to

figure 5: A typical line of shops.

CHAISE LADOUSA

228 Language in Society 31:2 (2002)

flux than are other kinds. The point here is not that school advertising comprises

a domain in which script and language are in proper synchronization; linguistic

play, as illustrated above, occurs in all domains of advertising in North India and

figures in commentary that links various contextual factors of the message, prod-

uct, or location of advertisement with ideological dimensions of language. What

is present in the domain of school advertisement but not elsewhere is a set of

predetermined correlations (judged as proper) between linguistic representations

of persons, objects, or institutions and their manifestations in advertisements,

which, in turn, may be referenced in explanations of their correct functioning.

Hindi lexical items in Devanagari script and English lexical items in roman script

index polar opposites configured by language medium. This is possible because,

within school advertising, nationally derived distinctions (the boards) find their

place in local institutions (schools that claim their affiliation). We now turn to the

advertising habits of another institution – tutorial services – which utilizes lan-

guage difference in selling distinctions in school mediums.

ADVERTISING TUTORIALS

Schools are not the only educational institutions in North India that utilize ad-

vertising to attract students. Many parents explained to me that, in order to pass

their yearly exams, their children needed more instruction than school alone could

provide. Many called on the services of a “tuition” (tutor). Most of the families I

knew hired a tutor through family or neighborhood-based friendship connec-

tions. Many had a “cousin-brother” who was taking classes at Banaras Hindu

University or Kashi Vidyapith, the two local universities, who was either willing

to tutor or knew of someone else who might be. Families who approached a

tutorial service were the exceptions.

Nevertheless, advertising for tutorial services is intense. Tutorial services largely

utilize the same varied media as schools: signage around town and advertisements

in the newspaper.

16

Some tutorial service advertisements index the school me-

dium to which the service caters through the conjunction of lexical item and script.

Some, furthermore, index parallel and discrete medium affiliations in their bid to

attract students from both mediums – something that never happens in school ad-

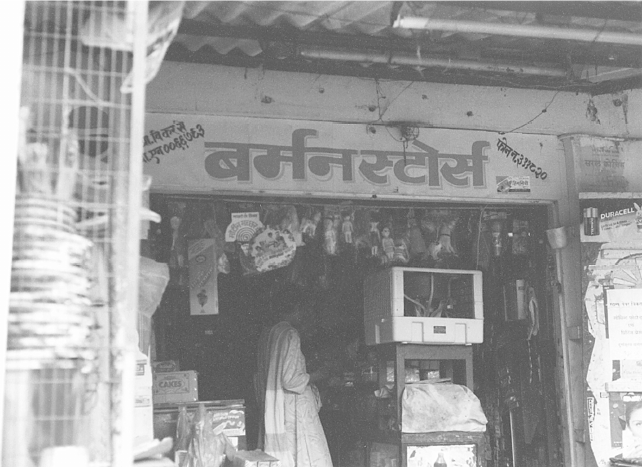

vertisements. The advertisement shown in Fig. 6 demonstrates that tutorial ser-

vice advertising is a realm for the creation of medium distinctions in which the

salience of conjunctions of Hindi and English lexical items, and Devanagari and

roman scripts, respectively, is apparent in a single message. This advertisement was

displayed high over the road. It is transliterated and translated as follows:

M. S. S. TUTORIALS sa¯yãka¯ l ‘M. S. S. Tutorials evening

kaksha¯ye˜ III se VIII u. pra. bor

.

d CBSE from level three to eight UP Board CBSE

ma¯ruti shiksha

.

n santha¯n raji. Maruti Learning Institute Raji.

B-31/36 sanka

.

t mocan mandir ke pa¯s B-31036 near the Sankatmochan Temple

bhoga¯bı¯rva¯ra¯

.

nası¯ Bhogabir Banaras’

ADVERTISING IN THE PERIPHERY

Language in Society 31:2 (2002) 229

Abbreviations such as “M. S. S.” are not uncommon in North India. Nita Kumar’s

experience with such abbreviations is worth quoting:

“I am the daughter of the I. G.” The man was a fresh recruit and didn’t grasp the

meaning of what I said, but he took me through the inspector’s empty office,

nodding at questioning countenances on the way, “She’s a big person.” In fact,

it wasn’t the I. G. that was crucial; any two or three initials would do. As for

reaching closed places, if we had a jeep all we needed to do was to put a large

plate on the front reading “R. S. C., Varanasi City” (Research Scholars from

Chicago) to match such signs as “A. D. M.” (Additional District Magistrate),

“C. S. C.” (Civil Surgeon City), “C. E. E.” (Chief Executive Engineer), “U. P.

S. E. B. M. D.” and the plates of other VIPSs who could reach places. (Kumar

1992:120)

Although Kumar is speaking of abbreviations attached to offices of power whose

physical manifestations seem to require an automobile, her reflections nicely

illustrate the degree to which such abbreviations are used in North India. Perhaps

what letters were actually used in her example was inconsequential precisely

because their ability to denote power was presupposed, triggered by their pres-

ence on the plate of a car.

17

In other contextual renditions, what is denoted by the

initials has a broader range than rank, government service occupation, or office;

abbreviations are not confined to official, power-laden domains. Political parties,

companies, and commercial products, as well as standard tokens of everyday

reference (STD, standard trunk dialing, is used for the public pay telephone) are

commonly named by abbreviations.

Fig. 6 is presented here because it displays the conjunction of language of

representation and script that one not well versed in the range of possibilities

within advertising in North India might expect. English terms are presented in

roman script, and Hindi terms in Devanagari. Even so, interesting processes are

at play in the advertisement, especially concerning the relationship between what

is referenced and its appearance as Hindi or English. An abbreviation suffices as

the name of the company; not until the third line does one find out what the

abbreviation stands for. Roman letters come to stand for Hindi words (the last of

which, santha¯n, is misspelled, and should be sanstha¯n). The letters are followed

by the roman-rendered English, “Tutorials.” Without the information provided

beyond the first line of the sign, one would have no idea that the company name

is comprised largely of Hindi words.

The time of availability, ‘evening’ (sa¯yãka¯l ), is indicated in Devanagari-

rendered Hindi, as is ‘levels’ (kaks´a¯ ye˜ ) on the next line. Roman numerals

denote the grade levels served. The abbreviations for board affiliations are tell-

ing: ‘UP Board’ is rendered in Devanagari, but also in an abbreviated Hindi.

The sign could have said yu¯ pı¯ bor

.

d, which would have given a Devanagari

rendition of the roman characters (a not unusual practice). For that matter, it

could have said, “UP Board.” However, it preserves a perfect dichotomy be-

CHAISE LADOUSA

230 Language in Society 31:2 (2002)

tween Hindi0Devanagari and English0roman script, precisely because it de-

picts ‘UP Board’ in a less abbreviated form in which Devanagari represents an

abbreviated Hindi and not an abbreviated English. ‘CBSE’, an abbreviation for

a board that specifically oversees the requirements of some English-medium

fees-taking schools, is left unexpanded. The actual name of the institute comes

next, but not until the third line of the advertisement. Raji most likely stands

for ‘registered’. The address is split between the block designation and the

number (B-31036) and the neighborhood (Bhogabir), typical in North India.

Finally, and perhaps most important, the location of the institute is placed near

an important landmark, the Sankatmochan Temple, not far from Lanka.

18

The only exception in the sign in terms of the correspondence between De-

vanagari and Hindi on the one hand, and roman and English on the other, is in the

title of the company. The divergence is particularly apparent in a sign that other-

wise precisely preserves correlation between Hindi and English lexical items,

and Devanagari and roman scripts, respectively. Two factors lend the divergence

meaning – one in the domain of linguistic practice within advertising in general,

and the other present in the sign itself and spatially configured. Advertisements

frequently use roman initials as a company’s name, and these initials may stand

for either English or Hindi lexical items. Advertisements may also employ De-

vanagari to represent Hindi or English lexical items.

19

The spatial configuration

figure 6: Advertisement for a tutorial service.

ADVERTISING IN THE PERIPHERY

Language in Society 31:2 (2002) 231

of abbreviation and corresponding lexical item in Fig. 6 reminds one of Kumar’s

impression that the abbreviation itself carries persuasive force; here, it is what

one encounters first in the sign, only later to be explained.

The relationship between abbreviation and the language it indexes is a bit

more complicated in Fig. 6 than in Kumar’s examples, for two reasons. First, the

abbreviations do not index languages in the manner typical of the rest of the sign.

In other words, “M. S. S.” refers to the letters that would begin a roman script

rendition of the unambiguously Hindi name of the company. An act of translation

has occurred in the sign, one essentially different from that entailed in the ren-

dering u pra for Uttar Pradesh, or CBSE for the Central Board of Secondary

Education (line two). Thus, within the rest of the sign’s own construction of a

properly functioning language-indexing script, “M. S. S.” is marked or unusual.

Second, the renditions in lines one and three do not match. One who understands

both Hindi and English

20

and the conventions for their abbreviation is left won-

dering whether the company’s name is ma¯ ruti s´iks´a

.

n sanstha¯n TUTORIALS

(‘Maruti learning institute tutorials’). But precisely this discrepancy exposes the

language processes at work. The title as rendered on the first line is not an English

equivalent of the information present in the rest of the sign (unreadable to anyone

nonliterate in Hindi). In fact, as shown above, the sign drives home the need to

keep separate Hindi and English, and the scripts that properly index them. This

makes the title odd and therefore noticeable.

That the marked or referentially charged item in the advertisement appears

first is no accident: Abbreviations are popular means of identification in North

India for everything from government offices to personal names. However, whereas

those examples can demonstrate the easy representation of “Hindi sounds” with

English-based orthographic representation, and “English sounds” with Hindi-

based representation, such that scripts’language-indexing functions blur, the sign

examined here represents a domain where those functions have been constructed

“on the spot.” Furthermore, it illustrates that in North India, scripts’ language-

indexing functions can be used to effects other than language-indexing.A roman-

script-based translation of sounds that begin Hindi words appears first in a sign

that later works to keep script and language in strict correspondence (Devanagari0

Hindi vs. roman0English). For the Hindi-reading public implied by the sign’s use

of Hindi in all but two abbreviations and one word, English is the language of

catchy identification and semiotic innovation.

ADVERTISING THE LOCAL, ADVERTISING THE NATIONAL

The advertisements for educational institutions that clog Banaras’s public spaces

are not the only such advertisements in town; newspaper readers encounter them,

too. Newspapers, like schools, are divided according to language medium,

21

avail-

able in Hindi, Urdu, English, and some other languages in Banaras, even if they

are not produced there. Educational advertising is confined largely to nationally

CHAISE LADOUSA

232 Language in Society 31:2 (2002)

distributed dailies, which contain sections that focus on major metropolitan areas

in India and their environs, apart from strictly national news; the section covering

Banaras comes from either Delhi or Lucknow.

22

Most of the institutions advertised in the newspaper read in Banaras exist

elsewhere, in cosmopolitan cities like Delhi, Mumbai, and Chennai. Concomi-

tantly, the indexical plurality provided by lexical0script combinations prevalent

around town is absent from the newspaper. Only one possibility exists in the

national daily: English lexical items written in roman script. Examples presented

below demonstrate that advertisements emanating from the center for institutions

located there index Banaras and its educational institutions in two ways. On one

hand, national advertising for educational institutions corresponds to the adver-

tising practices of only the most expensive English-medium schools in Banaras,

because only they produce advertisements in English rendered in roman script.

Expensive English-medium schools in Banaras, thus, are indexical of the center,

and other schools in Banaras are not. On the other hand, national advertising

indexes Banaras as a place on the periphery, because medium distinctions, a large

part of the indexical labor done by lexical0script combinations around Banaras,

are wholly absent in newspaper advertising for educational institutions. In Ba-

naras, some parents of children enrolled in English-medium schools and other

people who read English newspapers explained to me that, in comparison with

newspaper advertisements for schools, school advertisements encountered dur-

ing a walk around town look disordered.

Like local advertising for education, advertising in the national daily is pro-

duced by both schools and tutorial services. In the newspaper, however, tutorial

services’ advertising strategies differ from schools’ more significantly. No local

schools advertised in the nationally distributed dailies widely available in Ba-

naras. No local tutorial services did, either, but the correspondence-based lessons

offered by some tutorial services extend to Banaras. Some prestigious schools

with national reputations advertise in national dailies, but these differ from tuto-

rial services’national advertising practices in one crucial way.

23

Prestigious schools

that advertise in national papers ostensibly draw students from all over India (in

the case of boarding schools) or from the major urban centers in which they are

located (day schools). Nationally-advertised tutorial services, however, may reach

out to students living all over India. The latter often have branches in several

urban areas, sometimes nationwide. Sometimes tutorial services advertise na-

tionally for only one location (usually in a major urban center), and sometimes

institutes offer correspondence courses toward a degree, but these seem to be

exceptions.

The prototypical elite schools for Indians are boarding schools, many estab-

lished during the period of British rule. These schools draw students from all over

India. They represent the paradigmatic institutionalization of English in the mod-

ern postcolonial Indian setting as a cross-over language uniting state or region-

based languages. Some major urban areas have English-medium schools that

ADVERTISING IN THE PERIPHERY

Language in Society 31:2 (2002) 233

advertise in widely distributed dailies but draw their students primarily from their

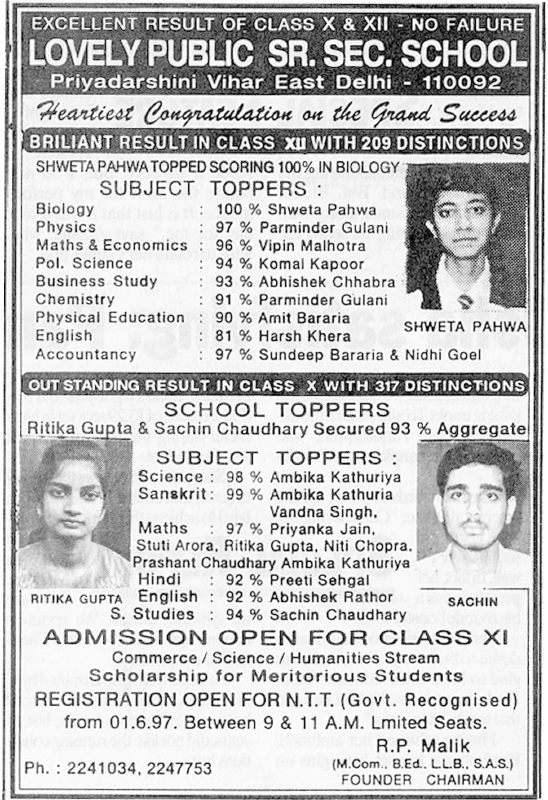

own urban centers. Such a school’s advertisement appears here as Fig. 7.

Most attention-getting in the advertisement are the faces of students who have

been particularly successful in exam scores. The first student is commended for

figure 7: Advertisement for a school in Delhi in a locally distributed national

daily; from India Express, Lucknow (8 June 1997).

CHAISE LADOUSA

234 Language in Society 31:2 (2002)

her perfect score in biology, and the next two students for their high scores over

all. Top-scoring students were not absent from Banaras schools, but their pictures

were not used in advertising.

24

Rather, photographs of students making top scores

on exams would be published in the yearbooks produced by both schools focused

on in this study, which were distributed to students and their families and not used

for general advertising. The rest of the advertisement in Fig. 7 is typical for

schools that advertise in nationally distributed papers. High results from class

twelve are separated from class ten because these crucial exam-taking points in a

student’s career largely determine in which “line” the student will continue. The

actual percentage scores received are listed. All schools that advertise mention

that their students receive top scores on exams, but not all are as meticulous or

comprehensive as the one in Fig. 7. The lines or “streams” are listed toward the

bottom: “Commerce,”“Science,” and “Humanities.” Class ten results are as cru-

cial as those of college-going class twelve students, and this fact is displayed by

the announcement “ADMISSION OPEN FOR CLASS XI.” Entrance to class

eleven is based largely on the results of exams taken on completion of class ten.

“NO FAILURE” is proclaimed, and there is not a hint of Hindi in the advertisement.

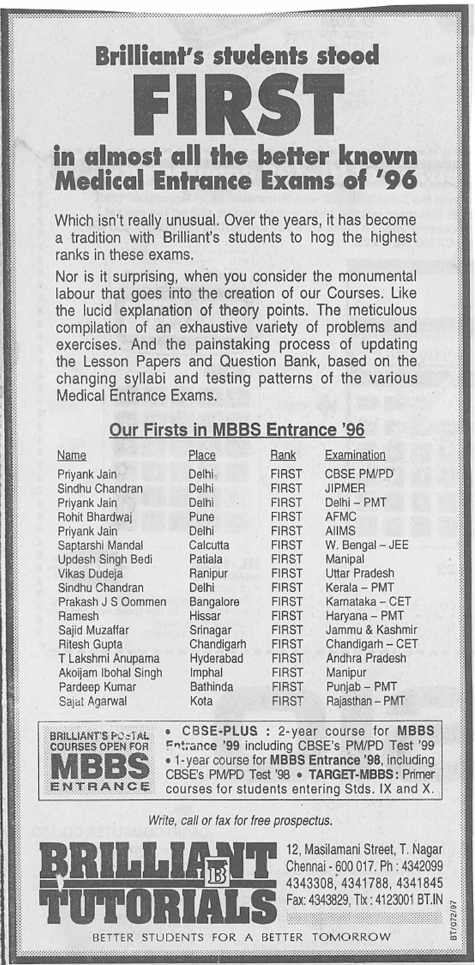

What is immediately apparent in many advertisements for tutorial services

is the bewildering array of educational boards across the country. Fig. 8, an

advertisement for a tutorial service that helps students gain entrance to col-

leges with a medical focus, is typical for tutorial services that advertise nation-

ally. It emphasizes the success its students have attained. “First” is the largest

word in the advertisement, and the explanation before the list of exemplary

students flourishes a lexicon of success. The students are able to “hog the high-

est ranks” because of the “monumental labour” of the tutorials. Most relevant

to this discussion of advertising is the next section, which lists the “firsts” in

the medical entrance exam who have been associated with the tutorial service

and the cities where the students took the exam. The most common city is

Delhi, but there are others, giving the advertisement national appeal. The “rank”

category is redundant, but this redundancy is effective as an advertising tool:

All students have ranked “first.” The last column translates location into the

idiom of educational institutions, specifying the testing board for each student.

As in Fig. 7, more than one board is mentioned, but the boards in Fig. 8 have

lost the element of local competitiveness and, instead, are present to add to the

tutorial service’s proof of success. State boards and private boards mingle with-

out any comparative frame.

Though many places and tests are named, the CBSE is mentioned first in the

list. One cannot attribute that position to the student’s homes in the national cap-

ital, because many of the students taking other tests hail from Delhi. CBSE is also

mentioned first in the box, just under the list of model students, and again later. It

is the only board mentioned in the advertisement’s copy. In light of the CBSE’s

national popularity, it is no surprise that, in Banaras, it is the board to which

schools’ affiliations are often claimed to be false.

ADVERTISING IN THE PERIPHERY

Language in Society 31:2 (2002) 235

figure 8: Advertisement for a tutorial service in a locally distributed national

daily; from India Express, Lucknow (8 June 1997).

CHAISE LADOUSA

236 Language in Society 31:2 (2002)

Although, at the national level of educational identity, the CBSE is particu-

larly valued,

25

it is only one board among many. This advertisement mentions

that one of the reasons the tutorial service is so successful is related to the lack of

uniformity among the various boards’ exams: “And the painstaking process of

updating the Lesson Papers and Question Bank, based on the changing syllabi

and testing patterns of the various Medical Entrance Exams.” Here, the adver-

tisement presents the nation’s complement of educational boards as a disorderly

bunch that requires diverse knowledge on the part of the centralized tutorial ser-

vice. Most obviously, and most unlike the advertisement depicted in Fig. 6, Fig. 8

contains no Hindi. As in Fig. 7, English is the sole medium of advertising. Fig. 7

comes from Delhi, and Fig. 8 from Chennai in South India.

26

As with the boards

and newspaper language mediums that contain them, the school’s and tutorial

service’s advertisements are clearly supralocal messages, but in different ways. If

one attends the school advertised in Fig. 7, one might excel in Hindi, but only as

one subject among many requiring examination in the board’s structure. The

message that English is the language of success is unambiguous. This is true also

of the tutorial service, but whereas the school is a local institution of national

(linguistic) scope, the tutorial service is simply a national institution that has

become so by catering to diverse exam requirement structures. Both have enacted

their sales pitches through English; within these, a discourse of rivalry like that

established in Fig. 6 is not possible.

CONCLUSION

Whether discursive activity about schools occurs in Banaras within spoken dis-

course or within printed advertising entails different possibilities for the con-

struction of the relationship among language variety, language value, and language

community. In spoken discourse, multiple constructions of Hindi- and English-

medium schools as indexes of centrality and peripherality are possible. In terms

of economic opportunity, English-medium schools provide conduits to a center

to which Banaras residents look, and Hindi-medium schools lie in the periphery

because of their lack of possibilities. In terms of nationalism, Hindi-medium

schools locate Banaras in the center, and English-medium schools suggest a pe-

ripheral stance suspected of lacking patriotism. In spoken discourse generally,

Hindi- and English-medium schools are contested, and they are productive of

differences that betray a unified hierarchical principle.

In printed advertising, the centrality of English and the English-medium schools

for which it is employed is more certain. In order to explain what makes English

so decisively indexical of the center in advertising, one must include more than

language distinctions per se. Script distinctions matter too, and they mingle with

language distinctions to produce an indexical regimentation of the center and its

periphery. A process occurs in advertising for schools in the newspaper in which

adherence or nonadherence to only one possibility of lexical0script alignment

ADVERTISING IN THE PERIPHERY

Language in Society 31:2 (2002) 237

(English0roman) establishes the indexical ground of the metalinguistic judgment

of what is centerlike and what lies on the periphery. Peripherality’s indexical

salience in advertisements for educational institutions in Banaras is constructed

by newspapers that are published elsewhere; advertising done by schools and

tutorial services in Banaras confirms that the city lies at the fringe of an all-

English possibility. Consistently, a look in the newspaper, where advertisements

for institutions at the “center” can be found, confirms that English lexical items in

roman script are the only ones present, whereas a quick walk around town expo-

ses one to other combinations. School and tutorial service advertising’s message

for Banaras’s newspaper-reading residents is clear: Places elsewhere are for an

English unadulterated by Hindi, whereas Banaras as a whole is subordinate to

such locations precisely because, in Banaras, languages and their institutions are

visibly plural and in contest.

NOTES

*This article is based upon research conducted between October, 1996 and October, 1997 in

Banaras and Delhi. Funds for research were provided by the National Science Foundation. The article

is an expanded version of a paper presented at the American Anthropological Association’s Annual

Meeting, 1999, held in Chicago, IL. I would like to thank Rakesh Ranjan and Ravinder Gargesh for

guidance and friendship in India. For close reading and criticism of drafts, I would like to thank Ann

Gold, Nita Kumar, Bonnie Urciuoli, David Lelyveld, and especially Susan Wadley. Joanna Giansanti

helped considerably with the graphics and figures. I would also like to thank anonymous reviewers,

one of whose comments were especially detailed, and the editor for her advice and encouragement.

1

Although some scholars have included language in their discussions of politics in India, few have

explicitly focused on language in education as an ethnographically approachable topic. Schooling and

matters of education are often mentioned and described in ethnographic writing on North India (e.g.,

Minturn 1993, Wadley 1994, Jeffery & Jeffery 1997), but a systematic treatment of relations between

language and education in India is yet to be done. The relationship between gender and education is

the explicit focus of essays in Mukhopadhyay & Seymour 1994, as well as of Kumar’s (1994) his-

torical consideration of schools in Banaras.

2

For Hindi’s increasing separation from Urdu and the former’s association with Hindu identity

and the latter’s with Muslim identity, see Rai 1984, Lelyveld 1993, King 1994, and Dalmia 1997. For

the ways that colonial projects enlisted linguistic distinctions, often with the result of increasing their

association with religious distinctions, see Raheja 1996 and Cohn 1997.

3

See Masica 1991 for a grammatical treatment of variation in the Hindi Belt and beyond.

4

Simon 1986 analyzes the ways that residents of Banaras utilize both Bhojpurı¯ and Hindi, some-

times within a single interaction, so that switching is a potential realm with its own metapragmatic

effects.

5

For a historical treatment of the use of languages in educational institutions in India, especially

in the transition from the colonial to the postcolonial world, see Kumar 1991. For the importance of

official policy regarding language and education for those engaged in pedagogy, see Khubchandani

1983 (especially chap. 4) and 1997.

6

Woolard 1985 problematizes Bourdieu’s notion of dominance within a market by pointing to

salient notions of resistance mobilized by “dominated” practices. Discourse about medium in North

India joins her critique in that its configurations of dominance are multiple and its possibilities for

resistance complex.

7

See the preceding discussion of the three language formula, however, for reasons that regions

outside the Hindi Belt have not shared enthusiasm for Hindi as India’s national language.

8

For an explanation of the RSS’s relationship to another Hindu organization, the VHP (Vishva

Hindu Parishad), and political party, the BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party), see Basu 1996.

CHAISE LADOUSA

238 Language in Society 31:2 (2002)

9

Some parents, and nearly all teachers at schools of either medium, explicitly identified Banaras

itself as the center, pointing to the city’s role in the standardization of Hindi and the development of

a literary legacy (Dalmia 1997, King 1994). All of the people who pointed to Banaras as the origin of

modern Hindi, however, acknowledged that such activities have now passed into the hands of the

government.

10

Irvine 1989 critiques Bourdieu’s conceptualization of dominance across markets for his lack of

attention to this kind of difference between spheres of communicative activity: “It [Bourdieu’s con-

ceptualization] tends to reduce language to presuppositional indexicality and to derive language’s

role in political economy entirely therefrom” (1989:256).

11

Devanagari, Hindi’s writing system, has as an ancestor the Brahmi script once modified for use

with Sanskrit. For a description of Devanagari’s evolution, see Masica (1991:133–51). Masica ex-

plains that “Nagari (literally the “city” or “metropolitan” script , nagar ‘city’, also called Devana-

gari) is the official script of Hindi, Marathi, and Nepali, and of the new (or revived) literatures in

Rajasthani, Dogri, Maithili (and other Bihari dialects), and Pahari dialects (e.g., Kumauni) when

written” (1991:144).

12

Notice the gap between the predominance of English-medium advertised schools and the virtual

absence of Hindi-medium advertised schools, and the political rhetoric of officials (Mulayam Singh

Yadav, former chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, was the primary official discussed during my stay)

against English as a foreign language of the colonizer. Many middle- and upper-class people ex-

plained to me that such moves were useless because advertising showed that people obviously wanted

English-medium education, or harmful because they only incited the uneducated to anger. Notice the

process by which the government system of schools is left out of the picture by middle- and upper-

class reactions to criticism, as well as by the practice of advertising. In turn, during my fieldwork, this

gap was described as a “craze” for English-medium education.

13

Thus, perhaps ironically, the school that includes strictly English lexical items and roman script

in its written advertisements is the only type of school that involves nonliterate persons in its public

exposure, through television, which has become a rather natural indication of middle-class status in

Banaras; however, televisions exist in public spaces as well, where they are watched by much larger

audiences.

14

This example illustrates particularly well the ways that visual advertising uses script difference

to represent language difference. In interactions between clerks and customers, I heard entire con-

versations in Hindi in which the brand names of cigarettes or other items were the only lexical items

that might be identified as English. These cannot be called examples of code-switching, but in their

visual representations, such as the cigarette advertisement in front of the store, items’representations

are clearly demarcated as English.

15