Road and Access Law:

Researching and Resolving Common Disputes

All rights reserved. These materials may not be reproduced without written permission

from NBI, Inc. To order additional copies or for general information please contact our

Customer Service Department at (800) 930-6182 or online at www.NBI-sems.com.

For information on how to become a faculty member for one of our seminars, contact the

Planning Department at the address below, by calling (800) 777-8707, or emailing us at

This publication is designed to provide general information prepared by professionals in

regard to subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not

engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. Although prepared

by professionals, this publication should not be utilized as a substitute for professional

service in specific situations. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the

services of a professional should be sought.

Copyright 2007

NBI, Inc.

PO Box 3067

Eau Claire, WI 54702

38512

National Business Institute is a division of NBI, Inc. and is not in any way affiliated with the

National Business Institute, Inc. of Atlanta, Georgia.

Any West copyrighted materials that are included in this manual are reprinted with

permission.

Are you

maximizing

the visibility of your

company?

SPONSORSHIPS

Let us help you.

Savvy businesses know they need to take every opportunity to get their company

and products in front of the right audience. NBI

is

that opportunity.

By sponsoring break times at NBI seminars, you’re taking advantage of yet another

way to establish relationships with new customers – and solidify your contact with

those you already have.

Why pass up this opportunity when reaching our shared audience is so easy?

Call us today to find out more about how you can become a sponsor for an

NBI seminar.

Legal Product Specialist

Laurie Johnston

800.777.8707

IN-HOUSE TRAINING

Can training your staff be

easy and individualized?

It can be with NBI.

Your company is unique, and so are your training needs. Let NBI tailor the content

of a training program to address the topics and challenges that are relevant to you.

With customized in-house training we will work with you to create a program that

helps you meet your particular training objectives. For maximum convenience, we’ll

bring the training session right where you need it…to your office. Whether you

need to train 5 or 500 employees, we’ll help you get everyone up to speed on the

topics that impact your organization most!

Spend your valuable time and money on the information and skills you really need!

Call us today and we will begin putting our training solutions to work for you.

Legal Product Specialists

Jim Lau Laurie Johnston

800.777.8707

Road and Access Law:

Researching and Resolving Common Disputes

Authors

A. McCampbell Gibson

Alston & Bird LLP

One Atlantic Center

1201 West Peachtree Street

Atlanta, GA

James A. Langlais

Alston & Bird LLP

One Atlantic Center

1201 West Peachtree Street

Atlanta, GA

Dale R. Samuels

Jarrard & Davis, LLP

105 Pilgrim Village Drive, Suite 200

Cummings, GA

PRESENTERS

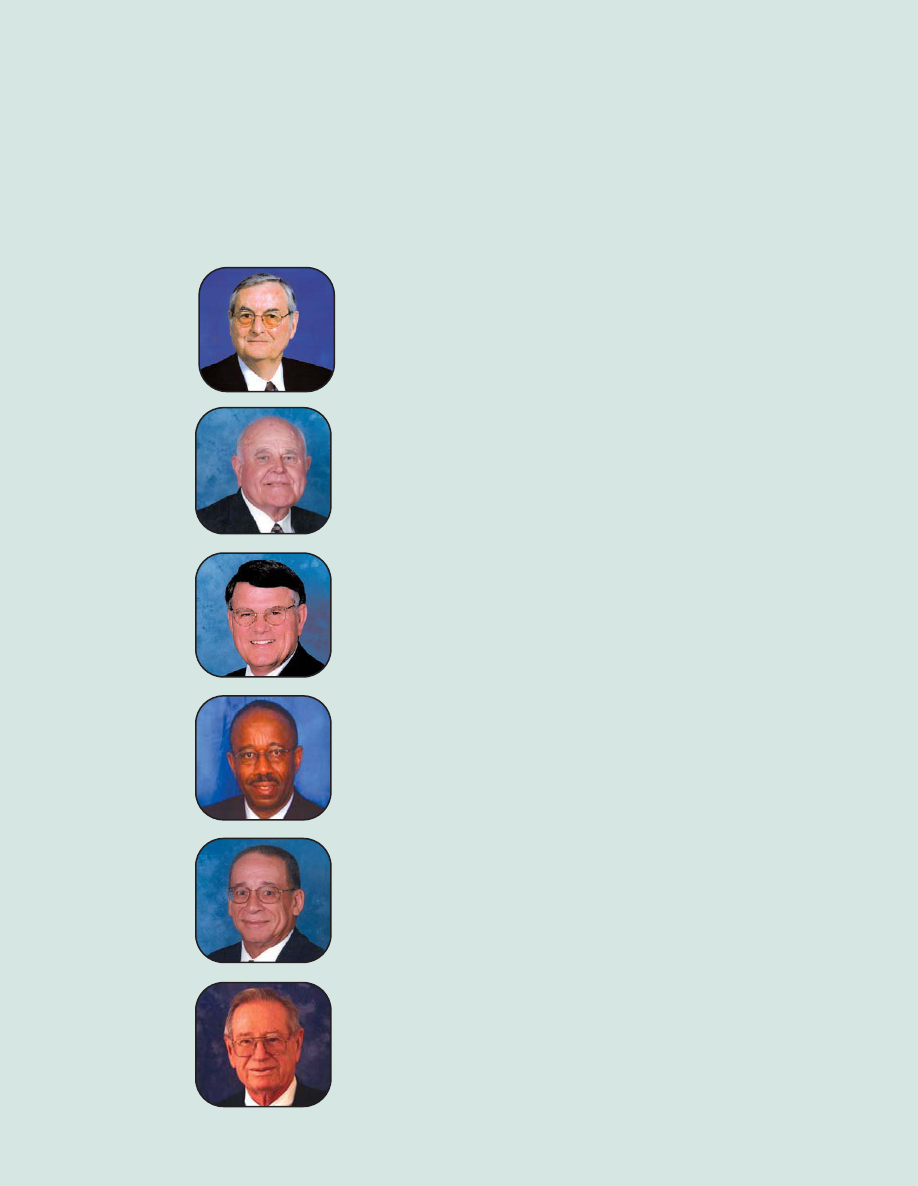

A. McCAMPBELL GIBSON is a partner in with Alston & Bird LLP's litigation and trial

practice group. He co-chairs the group's Real Estate Litigation Team. Mr. Gibson has been

named a Georgia Super Lawyer in Real Estate Litigation in 2006 and 2007. He concentrates on

complex commercial litigation with an emphasis on real estate disputes. He represents and

counsels national retailers, developers, mall, hotel and office owners, property management

companies, petroleum companies, restaurants, and convenience stores in and contract

enforcement, restrictive covenant and brokerage disputes. Mr. Gibson is a member of the

International Council of Shopping Centers and Leadership Georgia. Mr. Gibson also devotes a

significant amount of time to defending companies from toxic tort and project liability claims,

involving alleged personal injuries (e.g., exposure to chlorine, welding fumes and pesticides) and

property damage (e.g., alleged adhesive failure and printing press damage). Mr. Gibson received

his B.A. degree, magna cum laude, from Washington & Lee University. He received his J.D.

degree, cum laude, from the University of Georgia, where he was an editor for the Georgia Law

Review. Mr. Gibson wrote Gibson and Pearson, "Enough is Enough! - the Scope of the

'Perpetual' Right to Cure," and Gibson and Stroud, "Do I Have Manganism or Parkinson's

Disease?: Causation Hurdles in Proving an Association Between Welding Fumes and Disparate

Neurological Disorders," Mealey's Welding Rod Litigation Reporter.

JAMES A. LANGLAIS is a partner in the Environmental and Land Use Group and the Toxic

Tort Group at Alston & Bird LLP in the firm's Atlanta office. His practice focuses on complex

toxic torts, mass torts and environmental litigation. He also represents clients in land use and

business litigation matters. Mr. Langlais routinely represents clients in toxic tort and mass tort

cases and cost recovery/contribution cases in federal and state courts. He drafted the Ethics

Ordinance for the newly-formed city of Sandy Springs, Georgia and was recently appointed the

Chair of the Sandy Springs Ethics Board. He also counsels the newly-formed city of Milton,

Georgia with respect to the promulgation of its own ethics ordinance and Ethics Board

procedural rules. Mr. Langlais has published about environmental and toxic tort matters in such

publications as Mealey's Emerging Toxic Torts and The State Bar of Georgia Environmental

Newsletter, and speaks before professional organizations such as the State Bar of Georgia. Mr.

Langlais was selected to be included in the 2007 edition of The Best Lawyers in America in the

specialty of Mass Tort Litigation. He received his B.S. degree and his M.B.A. degree, summa

cum laude with a concentration in environmental management, from the University of

Massachusetts and his J.D. degree from South Texas College of Law. Mr. Langlais is a member

of the State Bar of Texas and the State Bar of Georgia. He is admitted to practice in Georgia and

Texas.

DALE (BUBBA) R. SAMUELS is a partner in the law firm of Jarrard & Davis, LLP, where he

practices in the areas of government, real estate and land use law, particularly in the

representation of local governmental entities. Prior to joining the firm, he practiced law in South

Carolina where he served as county attorney for Florence County, South Carolina, and during his

tenure there, he served as the president of the South Carolina Association of County Attorneys.

In addition, Mr. Samuels served as an officer of the Government Law Section of the South

Carolina Bar, as a member of the Employment Law, Tax Law and Professional Responsibility

sections and as a voting member of the House of Delegates of the South Carolina Bar. He also

served as a judicial law clerk to the Honorable William T. Howell, Chief Judge of the South

Carolina Court of Appeals. Mr. Samuels earned his B.A. degree from the Florida State

University in Tallahassee, Florida, and J.D. degree from the University of South Carolina School

of Law.

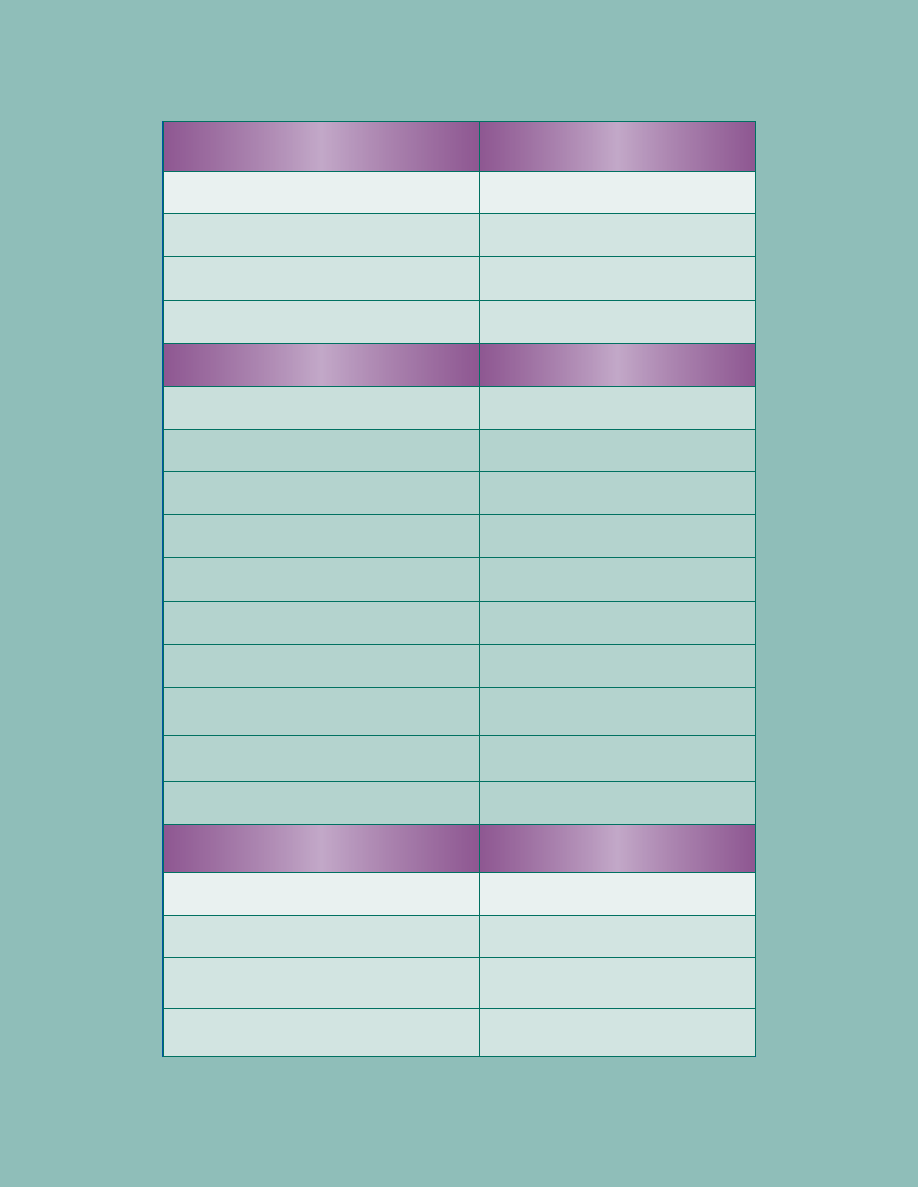

Table Of Contents

C

reation And Use Of Public Roads

1

3

P

rivate Roads In Georgia: Creation And Use

3

1

A

bandonment And Vacation Considerations

4

3

C

ontrol, Supervision And Management Of Roads And

H

ighways

5

5

R

oad And Access Pitfalls When Handling Real Estate

T

ransactions

14

3

C

ommon Road And Access Problems And Solutions

14

9

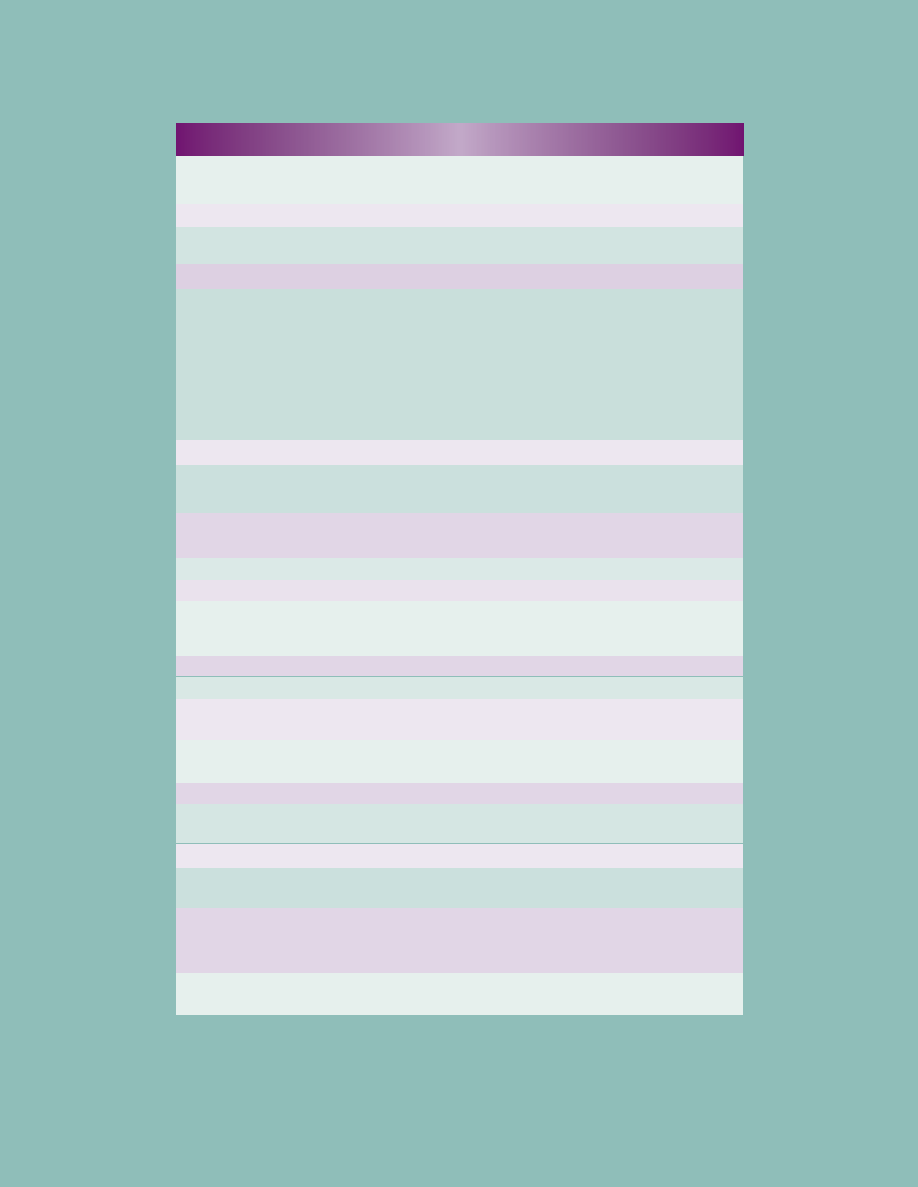

Creation And Use Of Public Roads

Submitted by Dale (Bubba) R. Samuels

• Special Circumstances Surrounding Public Roads

On Record

• Off Record: Is It Legitimately A Public Road?

• What Influences The Scope Of The Road Right Of

Way?

13

I. CREATION AND USE OF PUBLIC ROADS

The importance and affect of public roads on the ownership of land and the operation of

local government cannot be overstated. Public roads may fix one or more boundaries of a tract

of land, determine the legal right of access to a tract, and may constitute an easement in the title

across the interior of the tract. See generally

PINDAR'S GEORGIA REAL ESTATE LAW AND

PROCEDURE WITH FORMS § 5-1 (hereinafter “PINDAR’S”); see also 64 C.J.S. Municipal

Corporations § 1422. Further, public roads are also a major function of local governments which

are generally obligated to maintain, repair, record, and enforce right of ways on public roads.

See, e.g.

, O.C.G.A. §§ 9-6-21; 32-3-1 et seq.; Cherokee County v. McBride, 262 Ga. 460 (1992).

The following article explores the legal means and special circumstances surrounding public

road creation and the scope of a public road’s operation and affect on land ownership and the

authority of local government.

A. Special Circumstances Surrounding Public Roads on Record

Generally, “public road” as defined in State law is “a highway, road, street, avenue, toll

road, tollway, drive, detour, or other way open to the public and intended or used for its

enjoyment and for the passage of vehicles in any county or municipality of Georgia” including

those “public rights, structures, sidewalks, facilities, and appurtenances incidental to the

construction, maintenance, and enjoyment of such rights of way.” O.C.G.A. § 32-1-3 (24); see

also Chatham County v. Allen, 261 Ga. 177 (1991) (same); State Highway Board v. Baxter, 167

Ga. 124 (1928) (finding that the word “road’ in its popular sense includes overland ways of

every character, but has no fixed meaning in the law, depending on the context in which it

appears). Public roads may be constructed by private developers, counties, municipalities, the

state highway department, or by the federal government. P

INDAR'S § 5-3. Public roads in

14

Georgia are “legally” created by dedication, by prescription, by the express grant of an easement,

by deed, by special statutory proceeding, or by condemnation. See

O.C.G.A. §§ 32-3-3;

P

INDAR’S § 5-3; see also 64 C.J.S. Municipal Corporations § 1422.

For each of these types of methods of creation, special circumstances arise which may

influence whether a road has in fact become a public road and the legal affect of a created public

road. These factors can be categorized as “on-record” and “off-record” public roads. On-record

public roads are those roads that have been established by express grant, express dedication, or

by a government’s special statutory authority such as through its condemnation or purchasing

powers. See

O.C.G.A. § 33-3-3. Off-record public roads can be characterized as those roads

which have not been expressly granted to the public, but may be designated as public roads

through a sequence of provable facts and events which mandate that the road enter the public

domain. See, e.g.

, Jordan v. Way, 235 Ga. 496 (1975) (“Road may be public road

notwithstanding fact that it is not recorded with Department of Transportation.”); Baker v. State

,

92 Ga. App. 60 (1955) (“A highway may have its origin in a legislative act, or in order of court

of competent jurisdiction, or may come into existence by dedication or by prescription.”).

Importantly, if a road is considered a dedicated public road or an otherwise valid public

road on record, then a county may be compelled by mandamus to maintain the road “so that

ordinary loads, with ordinary ease and facility, can be continuously hauled over [it].” O.C.G.A.

§ 9-6-21; see also O.C.G.A. § 32-4-41 (1) (“A county shall plan, designate, improve, manage,

control, construct, and maintain an adequate county road system and shall have control of and

responsibility for all construction, maintenance, or other work related to the county road

system.”); Cherokee County v. McBride

, 262 Ga. 460 (1992); 40 C.J.S. Highways § 179 (noting

that construction, maintenance, and repair of public highways is a governmental function, and

15

insofar as repair and maintenance are concerned, a duty).

First, regarding public roads on record, local government authorities may expressly create

public roads by statute by acquiring roads via purchase, dedication, condemnation, donations,

and exchange of property. O.C.G.A. §§ 22-1-2; 32-3-3; 32-4-41; 32-4-90; 32-4-92; 36-34-3.

For example, Code Section 32-3-3 provides local governments broad powers to: (1) “accept

donations, transfers, or devises of land” from private and public entities “in fee or any lesser

interest”; (2) enter into agreements with private persons “for the exchange of real property or

interests therein for public road purposes”; (3) acquire roads by prescription; and (4) acquire

roads by dedication. However, although a local government may acquire public roads through

several means, a local government has an obligation to work with property owners to allow them

the highest and best use of their property. Tilley Props., Inc. v. Bartow County

, 261 Ga. 153

(1991). Further, a local government may not acquire property for future public purposes unless

it brings a substantial monetary saving, enhances the integration of highways, or forestalls the

physical or functional obsolescence of highways; but an entire lot, block, or tract may be

acquired although only part is needed if it is in the public interest. See, e.g.

, Fulton County v.

Davidson, 253 Ga. 734 (1985).

Second, a public road may come into existence through a dedication of a strip of land for

road purposes by an owner, evidenced by some action on the owner’s part, showing consent to

the abandonment of the owner’s dominion and dominion and control by the public. See

O.C.G.A. § 32-1-3(8) (defining “dedication” as “the donation by the owner, either expressly or

impliedly, and acceptance by the public of property for public road purposes, in accordance

with statutory or common-law purposes”); P

INDAR’S § 5-4. Generally, “[t]o prove a dedication

of land to public use, there must be an offer, either express or implied, by the owner of the land,

16

and an acceptance, either express or implied, by the appropriate public authorities or the

general public.” Smith v. State of Georgia

, 248 Ga. 154, 158 (1981); Ross v. Hall County

Commissioners, 235 Ga. 309 (1975); Carroll v. DeKalb County, 216 Ga. 663 (1961); Brown v.

City of East Point, 148 Ga. 85 (1918); see also O.C.G.A. § 44-5-230. To prove an offer of

dedication, “it must be shown that a property owner's acts clearly manifested an intention to

dedicate the property for public use.” Chandler v. Robinson

, 269 Ga. 881 (1998). Further,

“acceptance of an express offer to dedicate property may be shown by public use of the

property for a period of time sufficient to indicate that the public is acting on the basis of a

claimed right resulting from the dedicatory acts by the owner." Smith

, 248 Ga. at 160.

A typical example of express dedication is by express contract and deed. Generally,

where a dedication is made by deed, the grantor, the grantee, and the public are all parties to the

transaction. See PINDAR'S § 5-6; see also 26 C.J.S. Dedication § 15 (“The intent to dedicate

may be manifested by a deed. Such a deed may be from the dedicator to an individual, in

which the dedicator declares that a part of the land is subject to a public use, or it may except

some part of the land conveyed for a public use.”). Creation by contract includes deeds in

which the fee-simple title is conveyed to the strip in question, or other instruments granting an

easement for road purposes. P

INDAR'S § 5-6. Further, although a road deed may be valid

without a delineation of the area, it must contain language sufficient to designate with

reasonable certainty the land over which the road extends and a reference to a plat will not

suffice unless it can be determined from the plat exactly where the lines of the proposed road

will run. See

Ketchum v. Whitfield County, 270 Ga. 180 (1998) (finding that a deed dedicating

a road does not need to contain a perfect legal description, and the deed and dedication will be

valid so long as the description provides sufficient keys to determine the boundaries by

17

extrinsic evidence); DOT v. Howard, 245 Ga. 96 (1980) (finding that highway deed to DOT

was invalid where true legal title was in the grantor's wife, and could not be color of title

because of indefinite description); State Highway Dep’t v. Blalock

, 214 Ga. 29 (1958);

P

INDAR’S § 5-7.

Another common example of an offer of express dedication is the recordation of a

subdivision plat by a developer showing designated streets. See

Smith, 248 Ga. at 158

(“Where the owner of a tract of land subdivides it into lots and records a map or plat showing

such lots, with designated streets, and sells lots with reference to such map or plat, the owner

will be presumed to have expressly dedicated the streets designated on the map to the public.”);

26 C.J.S. Dedication § 17 (“[A] survey and plat alone are sufficient to establish an offer to

dedicate if it is evident from the face of the plat that it was the intention of the proprietor to set

apart certain ground for public use.”). Further, even where a proposed dedication plat is

ambiguous, parol evidence, the surrounding circumstances and the subsequent conduct of the

public can be used to show the boundaries and extent of a dedication. See

Cobb County v.

Crew, 267 Ga. 525 (1997). However, even though an owner may have expressly offered to

dedicate a road via a recorded plat, dedication will not be complete until the public accepts the

express offer. See

Watson v. Clayton County, 214 Ga. App. 225 (1994) (finding that the

recordation of a plat of subdivision containing offers to dedicate streets does not in itself

constitute acceptance by the public authorities of the street because the street must be both

dedicated by a private property owner and accepted by a public authority before it becomes a

public street.); 26 C.J.S. Dedication § 17 (“The mere filing of plat or map . . . does not of itself

work a dedication of the land indicated as reserved for the public use.”). Finally, acceptance of

an offer of dedication will not be inferred if a local government fails to assess property taxes on

18

the road. See Hale v. City of Statham, 269 Ga. 817 (1998) (“Although exemption from

taxation is one factor to consider in determining whether a government has exercised control

over property, a tax map is insufficient as a matter of law to manifest acceptance.”).

In sum, a road may be dedicated by express grant or presumed by the recordation of a

subdivision plat. However, although these facts may raise a presumption of dedication on the

part of an owner, a local government must still evidence acceptance of the express offer of

dedication. Accordingly, general contract law principles apply to determinations of offers and

acceptances of dedications, with the preferred construction that which renders all the provisions

of the instrument operative and effective, thus carrying out the intention of the parties. See

26

C.J.S. Dedication § 15.

B. Off Record: Is it Legitimately a Public Road?

If a public road has not been legally created by express grant, express dedication, or by

statute, then a road may still be considered a public road if certain facts and circumstances

arise. These include the manifestation of an implied easement, implied dedication, or a

prescription.

First, it is well established that where title to a public road or highway is not shown to be

in the public by express grant, there is a presumption that it exists merely as an easement, under

which the base fee in the underlying ground remains in the adjacent owners. R.G. Foster & Co.

v. Fountain, 216 Ga. 113 (1960); Thomas v. Douglas, 165 Ga. App. 128 (1983); PINDAR’S § 5-

14; 26 C.J.S. Dedication § 68 (noting that where the owner of property makes a common law

dedication, the ultimate fee remains unaffected, neither the government, the municipality, nor

the public acquiring any interest other than that of a mere easement). If a public road exists by

mere easement, then the public is not entitled to rights in timber, minerals, or other rights in the

19

roadway. Smith v. City of Rome, 19 Ga. 89 (1855). In the great majority of cases, however,

an express grant or express dedication is by fee simple due to the substantial cost in

constructing and maintaining public streets and highways. See

PINDAR’S § 5-16.

Second, as noted above, a road may considered a public road via implied dedication if

two criteria are established: (1) the owner intended to dedicate the land for public use; and (2)

the public accepted the dedicated property. Chandler

, 269 Ga. at 881. However, “[w]hen an

implied dedication is claimed, the facts relied on must be such as to clearly indicate a purpose

on the part of the owner to abandon his personal dominion over the property and to divert it to a

definite public use.” Id.

; Dunaway v. Windsor, 197 Ga. 705 (1944) (finding that to infer an

intention to dedicate property to public use from owner's “acquiescence” in use of his property

by the public “acquiescence” means a tacit consent to acts or conditions, and implies a

knowledge of those things which are acquiesced). Thus, whether an implied dedication or

acceptance has taken place is a question for the trier of fact. Jackson v. Stone

, 210 Ga. App.

465, 466 (1993).

Generally, actions that have been found to constitute an implied dedication include the

owner’s allowance of public use of the road and the acquiescence of the owner to local

governing authorities to repair and maintain roads. Jergens v. Stanley

, 247 Ga. 543 (1981)

(finding seven-year use by the public as a road and working by county is sufficient to establish

a dedication); Hood v. Spruill

, 242 Ga. App. 44 (2000) (finding that whether roadway easement

over private land is private or public is determined by use of roadway). Importantly, however,

these facts are not conclusive to show that a road has been dedicated to public use. See, e.g.

,

Forehand v. Carter

, 270 Ga. 534 (1999) (finding that an owner who permits the county to

occasionally grade a part of an alley does not manifest an intention to dedicate the alley to

20

public use); Chatham County v. Allen, 261 Ga. 177 (1991) (finding that unopened,

undeveloped, proposed roads in subdivision do not become “public roads” which county is

obligated to maintain, solely by virtue of process of implied dedication and acceptance, and

county could not be required to develop such roads); Irwin County v. Owens

, 256 Ga. App. 359

(2002) (“The mere use of one's property by a small portion of the public, even for an extended

period of time, is not sufficient to authorize an inference that the property has been dedicated to

a public use.”); see also

Central of Georgia R.R. Co. v. DEC Associates, Inc., 231 Ga. App.

787 (1998) (finding that where 15 to 20 years have elapsed since the dedication of an easement

without the government exercising any control, the presumption of law arises that the donation

of the easement was declined by the governmental entity).

Moreover, simply because the disputed road is depicted on a Department of

Transportation map, or a local government has a policy of delivering gravel and grading private

roads upon request, does not by themselves establish dedication of a road as a public roadway.

See

Chandler, 269 Ga. at 881 (“[A] road's placement on an official highway map is

‘administrative . . . as between the state, counties and municipalities. Its purpose [is] not to

ascertain and fix the status of the public right of use of every road in Georgia.’ Hence, this

evidence also fails to support a claim of implied dedication.”); Jackson v. Stone

, 210 Ga. App.

465 (1993) (finding that owner retained control over who used road by specifically granting or

refusing easements to use road, that road was built at his own expense, and that county's policy

of delivering gravel and grading private roads upon request was not indication of road's

dedication to public); P

INDAR’S 5-4; 26 C.J.S. Dedication § 40; 32 A.L.R.2d 953. Therefore, in

sum, implied dedication will generally be found to have occurred if an owner allows

continuous public use for an extended period of time and permits local authorities to

21

continuously maintain the road for many years. See, e.g., Chandler, 269 Ga. at 881-82 (finding

no implied dedication because no maintenance performed on road in twenty-five years and only

on an occasional basis before then); Childs v. Sammons

, 272 Ga. 737, 738 (2000) (plaintiff did

not prove that occasional grading of 40 foot strip of road traversing defendant’s land dedicated

road to public use).

Finally, similar to implied dedication, a roadway may also be transformed into a public

road if acquired by prescription through continuous public use after seven years. See

O.C.G.A.

§§ 32-3-3(c) (“[A]ny state agency, county, or municipality is authorized to acquire by

prescription and to incorporate into its system of public roads any road on private land which

has come to be a public road by the exercise of unlimited public use for the preceding seven

years or more.”); 44-5-164; Chandler

, 269 Ga. at 882; A.C.L.R. Co. v. Sweatman, 81 Ga. App.

269 (1950). Thus, while a dedication implies a conveyance and an acceptance, a prescription

requires an unbroken possession or user under a claim of right. Dunaway v. Windsor

, 197 Ga.

705 (1944).

Generally,

[i]n order to obtain prescriptive rights over a roadway, the possession must

not originate in fraud, must be public, continuous, exclusive,

uninterrupted, peaceable, and accompanied by a claim of right. The use

must also be adverse rather than permissive, and in the case of public

roads acquired by prescription, public authorities must have either

accepted the road or exercised dominion over it. Lastly, there must have

been unlimited public use of the roadway for at least the seven years

preceding the claim of prescriptive acquisition.

Harbor Co. v. Copelan

, 256 Ga. App. 79 (2002) (quoting Chandler, 269 Ga. at 883). Similar to

implied dedication, courts have accordingly held that only continuous public use and

maintenance, as opposed to tenuous public use and infrequent public maintenance, is sufficient

to put an owner on notice of adverse use for a prescription. See

Chandler, 269 Ga. at 883

22

(finding that county did not acquire roadway by prescription where roadway was blocked and

impassable for approximately ten years prior to the property owners’ acquisition of property

and clearance of the roadway and use of road by neighboring property owner was permissive);

Jordan v. Way

, 235 Ga. 496 (1975) (finding that evidence showing road across owner's

property had been in existence for 74 years prior to its closing, that public used road in manner

adverse to owner continuously throughout such period, and that county authorities had repaired

road, was sufficient to support finding that public road had been established across owner's

property by prescription); Dunaway

, 197 Ga. at 705 (finding that evidence indicating that

trucks passing over land owner’s property from time to time and that the public authorities had

performed some work on the roadway, was insufficient to establish a continuous, uninterrupted,

and adverse use of the property by the public as a highway, as would be sufficient to establish a

highway by prescription); Harbor Co.

, 256 Ga. App. at 79 (finding that county did not acquire

title through prescription to a six-inch privately owned strip of land abutting county road and

covered by portion of privately constructed curbs and gutters, even if county accepted or

exercised dominion over curbs and gutters, where curbs and gutters were constructed with

express permission from owner of strip, and there was no evidence that county ever gave owner

of strip notice that it was asserting any claims adverse to his right of ownership ); Bass v.

Pearson, 219 Ga. App. 487 (1995) (“While there is evidence that numerous individuals used

that road and that the county had at some point graded and graveled the road, there is nothing

indicating when or for how long the county performed that work.”). Accordingly,

prescriptions, like implied dedications, require continuous adverse use by the public with a

coterminous claim of dominion and control over the road by local government.

23

C. What Influences the Scope of the Road Right of Way?

Another crucial area involving the creation, use, and operation of public roads is the

scope of a public road’s right of way. Generally, “right of way” is defined by statute as

“property or any interest therein, whether or not in the form of a strip, which is acquired for or

devoted to a public road.” O.C.G.A. § 32-1-3(25). The scope a public road right of way may be

influenced by several statutory provisions and common law factors which include (1) whether

the road is owned in fee simple by local government or the road is a mere easement for public

use; (2) the established width and parameters of public roadways; (3) the existence and rights of

abutting property owners; (4) utility line easements and urban servitudes; and (5) encroachments.

See

PINDAR’S §§ 5-13 through 5-25; 64 C.J.S. Municipal Corporations § 1462.

First, as noted above, a public road not dedicated to the public by express grant is

presumed to exist only as an easement, under which the base fee remains in the adjacent land

owners and the easement continues only as long as the public need for the road continues. See

Thomas v. Douglas, 165 Ga. App. 128 (1983); City of Atlanta v. Jones, 135 Ga. 376 (1910)

(holding that even a deed to a county or city may be subject to interpretation as to whether it

conveys a fee or a mere easement). As noted above, because of the costs of road maintenance,

most state and local governments acquire a fee simple title to the roadway, either by warranty

deed or by indefeasible fee authorized by statute. O.C.G.A. §§ 32-3-3; 32-4-41; 32-4-90; 32-4-

92; 36-34-3.

Second, the width of public roadways is generally determined by examination of the

deeds and records under which title to the road was acquired. Waller v. State Highway Dep’t

,

218 Ga. 605 (1963). Therefore, where a parcel of land of definite width is expressly dedicated as

a roadway, whether by deed, easement, subdivision plat, or otherwise, the width shown becomes

24

the official margin even though the actual part used and occupied for road purposes may be less.

Dover v. Pritchett

, 251 Ga. 842 (1984) (iron pins placed at corners of property said to prevail

over measurements to determine width of county road); Thurston v. City of Forest Park

, 211 Ga.

910 (1955). However, in cases where a public road has been established by implied dedication

or prescription, there is no presumption that the owner of the land on which the road traverses

intended to dedicate more than the public use requires. See, e.g.

, R.G. Foster & Co. v. Fountain,

216 Ga. 113 (1960) (finding that when dedication of a highway results from mere use and

acquiescence, it shall not to be inferred that the donor parted with more than the use necessitates,

therefore the evidence sustained verdict for landowner); Thrash v. Wood

, 215 Ga. 609 (1960)

(finding that parking area not included in dedication). Sidewalks are also considered part of a

public road, but dedication of an area solely for sidewalk purposes does not permit a government

from converting it into vehicular traffic without compensation to abutting property owners. R.G.

Foster, 216 Ga.113; see also Atlanta Muffler Shop v. McSwain, 98 Ga. App. 722 (1958)

(“Sidewalks are intended as public throughfares, and any person or corporation placing

obstructions on or over them in such manner as to render them dangerous to persons using them

in a normal manner is guilty of negligence.”). Finally, as noted in the statutory definition of

“public road,” a public roadway includes all “structures, sidewalks, facilities, and appurtenances

incidental to the construction, maintenance, and enjoyment of such rights of way.” O.C.G.A. §

32-1-3 (24). Accordingly, the width of a public right of way is determined by deed or the prior

public use of the right of way by the public in the absence of an express deed.

Third, the owners of land abutting a public road may influence a right of way and occupy

a special status as compared with members of the public generally. Generally, title to the

underlying fee of a street or road is prima facie vested in the abutting owners, unless conveyed or

25

transmitted to the public authorities. Fambro v. Davis, 256 Ga. 326 (1986) (noting that the fee in

all roads should be vested either exclusively in the owner of the adjacent land on one side of the

road, or in him as to one half of the road, and as to the other half, in the proprietor of the land on

the opposite side of the road). Further, subject to certain exceptions, and depending upon

whether the road is owned in fee simple or by easement, abutting owners may have special rights

of access, underground and overhead rights, and reversionary rights upon abandonment.

P

INDAR’S § 5-17; 64 C.J.S. Municipal Corporations § 1462 (“The owner of property abutting on

a public street has an easement over the street of light, air, and view, and an interference with his

right of privacy has been considered as an element going to make up his right to relief against an

encroachment on the highway.”). An abutting owner may also be subject to special obligations

not to obstruct passage, and may be liable for improvements on the roadway in some cases.

O.C.G.A. §§ 36-39-16; 36-39-20; P

INDAR’S § 5-17.

Importantly, abutting owners may have a special easement of access to their land over the

public right of way. See Barham v. Grant, 185 Ga. 601 (1937). The easement of access includes

the to reach the traveled part of the public road, but an owner is not entitled to enter at all points

along his boundary, provided the abutting owner is offered a convenient access to the premises.

See, e.g.

, State Highway Board v. Baxter, 167 Ga. 124 (1928) (finding that an abutting owner “is

not entitled, as against the public, to access to his land at all points in the boundary between it

and the highway, if the entire access has not been cut off, and if he is offered a convenient access

to his property and to improvements thereon, and his means of ingress and egress are not

substantially interfered with by the public”). Therefore, courts have concluded that curbing and

medians in the public right of way and regulation of traffic flow generally do not impair access

to an abutting owner’s property rights. See, e.g.

, Clark v. Clayton County, 133 Ga. App. 171

26

(1974) (finding that median change by closing front cross-over of owner’s hotel and opening

another 370 feet away did not interfere with owner’s ingress and egress); Dougherty County v.

Snelling, 132 Ga. App. 540 (1974) (finding that abutting owner has no rights to control traffic

flow, which is regulated for public safety); Johnson v. Burke County

, 101 Ga. App. 747 (1960)

(“[I]t conclusively appears . . . that the curb in question is so constructed and situated as to not

interfere with the right of the plaintiffs, their customers or others, in the matter of ingress and

egress.”). Finally, the right of access of abutting owners can be taken away from the abutting

owner by the exercise of the power of eminent domain and the establishment of limited-access

highways. See

O.C.G.A. §§ 22-1-2; 32-1-3(14) (defining limited access highway as “a public

highway, road, or street for through traffic, over, from, or to which owners or occupants of

abutting land or other persons have no right or easement or only a limited right or easement of

access, light, view, or air by reason of the fact that their property abuts upon such limited-access

highway, road, or street or for any other reason”).

Fourth, a public right of way may also be affected by the duty of local governments and

abutting property owners to keep the right of way free of encroachments. See

O.C.G.A. §§ 32-6-

1(a) (“It shall be unlawful for any person to obstruct, encroach upon, solicit the sale of any

merchandise on, or injure materially any part of any public road.”); 32-6-2 (authority to regulate

parking and unattended vehicles on public roads); Crider v. Kelly

, 232 Ga. 616 (1974) (finding

that DOT can require removal of any obstruction placed without express permission on road

within state's system and governing body of municipality can require removal of any such an

obstruction placed on city street not on state’s system).

Generally, encroachments on a right of way without the express permission of State or

local government is considered a “purpresture” and may constitute an abatable nuisance subject

27

to an injunction. See S.E. Pipeline Co. v. Garrett, 192 Ga. 817 (1941) (“The rule both in reason

and by authority is that, unless the public sustain or may sustain some degree of inconvenience

or annoyance in the use of a public highway or street or other public property, there is no public

nuisance.”); see also

Stephens v. State Highway Dep’t, 223 Ga. 713 (1967) (finding that an

inadvertent encroachment of less than one foot on the right of way would not require an

injunction which would in effect force demolition of the building). Courts have accordingly

found unauthorized encroachments as constituting an unlawful nuisance, including fuel tanks,

Williamson v. Souter

, 172 Ga. 364 (1931), pay telephones, City of Dalton v. Staten, 201 Ga. 754

(1947), newsstands, Magrill v. City of Atlanta

, 32 Ga. App. 5 (1924), and piles of debris.

Harbuck v. Richland Box Co.

, 204 Ga. 352 (1948). Thus, any unauthorized immobile structure

on a public road may constitute a public nuisance. See, e.g.

, Smith v. Hiawassee Hardware Co.,

167 Ga. App. 70 (1983) (“Structures on private property adjoining road rights-of-way only

become unlawful . . . if they obstruct a clear view of roads in such a manner as to constitute a

traffic hazard, and they are unauthorized.”) Williams v. Scruggs Co.

, 213 Ga. App. 470 (1994)

(finding plaintiff was unable to show that the allegedly vision-obstructing debris and heavy

equipment located on defendant’s property was “unauthorized”).

Finally, the right of way is also influenced by a local government’s power to regulate and

maintain utility lines. Generally, local governments are authorized by statute to license the use

of city and county streets for the transmission of utilities and for street railways so long as the

use of the public generally is not unreasonably interfered with. See, e.g.

, O.C.G.A. §§ 32-4-42

(“A county may grant permits and establish reasonable regulations for the installation,

construction, maintenance, renewal, removal, and relocation of pipes, mains, conduits, cables,

wires, poles, towers, traffic and other signals, and other equipment, facilities, or appliances of

28

any utility in, on, along, over, or under the public roads of the county . . . .”); 36-34-2 (regulation

of utilities by municipalities). Thus, although “the owner of the soil retains the exclusive right in

mines, quarries, springs of water, timber, and earth, . . . these rules must be taken with some

limitation as to the streets of a city. Certain uses . . . which are called ‘urban servitudes’ are the

necessary incidents of streets in large cities, and are paramount to the rights of the owner of the

fee.” City of Albany v. Lippitt

, 191 Ga. 756 (1941); PINDAR’S § 5-22.

Further, regulation of utilities and additional uses of the right of way for utilities may be

expanded over time. Faulker v. Georgia Power Co.

, 243 Ga. 649 (1979) (“A definition of land

to the public use as a street not only embraces all of the customary uses to which streets are

devoted at the time of the dedication, but will expand to take in all new uses that become

customary as civilization advances.”). Therefore, courts have found that the installation of

additional telephone wires, Kerlin v. Southern Bell Tel. Co.

, 191 Ga. 663 (1941), and facilities to

accommodate higher voltage electric lines, Humphries v. Georgia Power Co.

, 224 Ga. 128

(1968), amounted to a change in the degree of use rather than in the kind of use, so as not to

violate the existing right of way. However, while a local government may mandate that a utility

move utility lines to accommodate future road widening, it may not deny current permits based

on future potential use. DeKalb County v. Georgia Power Co.

, 249 Ga. 704 (1982) (electric

lines) (“The county may require the power company to move the power line to accommodate

future widening of [roads], but may not deny the power company a permit to locate the power

line within the right-of-way of that road because of speculation that [the road] may be widened at

some unspecified and unknown time in the future.”); City of Atlanta v. DeKalb County

, 196 Ga.

252 (1943) (water lines); P

INDAR’S § 5-22. In sum, State and local government may reasonably

regulate and license utility lines in the right of way subject to certain restrictions. See

O.C.G.A.

29

§§ 32-4-42; 36-34-2; 32-6-173.

30

Private Roads In Georgia: Creation And Use

Submitted by James A. Langlais

• Introduction

• Creating Private Roads Through Easements

• Difference Between Easements And Fee Estates,

Restrictive Covenants And Licenses

• Scope Of Easements

• Abandonment Or Forfeiture, Extinguishment

And Estoppel Of Easements

• Maintenance And Repair Of Easements

• Creation Of Private Roads Through

Condemnation

31

NATIONAL BUSINESS INSTITUTE

ROAD AND ACCESS LAW: RESEARCHING AND RESOLVING

COMMON DISPUTES

Atlanta, Georgia

July 17, 2007

PRIVATE ROADS IN GEORGIA: CREATION AND USE

James A. “Jim” Langlais

Alston & Bird, LLP

One Atlantic Station

1201 West Peachtree Street

Atlanta, Georgia 30309

(404) 8881-7490

A. Introduction

In Georgia, private roads may be created in a number of ways: by express grants, by

prescription, by necessity, and by private condemnation.

1

Procedures for creating private roads

such as these are intended to provide for an economically affordable and efficient method to gain

access to property.

2

In addition to providing landlocked property owners with mechanisms to

gain access to property, these procedures also seek to protect the interests of the servient estate

owner, i.e., the one burdened with the private road or easement.

3

This paper examines the

various types of mechanisms to create private roads in Georgia, as well as the legal issues related

to their creation, scope, maintenance and extinguishment.

B. Creating Private Roads through Easements

An easement is “a right in the owner of one parcel of land (i.e., the dominant estate

owner), by reason of such ownership, to use the land of another for a special purpose not

inconsistent with the general property in the servient estate owner”.

4

It is not a fee estate in land

or merely a contract right, but rather it is an interest in land owned or possessed by another; a

1

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-1; Jones v. Mauldin, 208 Ga. 14, 64 S.E.2d 452 (Ga., 1951) overruled on

other grounds.

2

Elk Horn Ranch, Inc. v. Board of County Com’rs, Crook County, 2002 W.Y. 167, 57 P.3d 1218

(Wyo. 2002).

3

Barge v. Sadler, 70 S.W.3d 683 (Tenn. 2002); Elk Horn Ranch, Inc. v. Board of County

Com’rs, Crook County, 2002 W.Y. 167, 57 P.3d 1218 (Wyo. 2002).

4

Brown v. Tomlinson, 246 Ga. 513, 272 S.E.2d 258 (1980); 25 Am. Jur. 2d, Easements and

Licenses § 1.

Hollomon v. Board of Education

, 168 Ga. 359, 147 S.E. 882 (1929).

32

privilege to enjoy and use the land of another.

5

Moreover, it may be created only by a person

with title to or an estate in the servient estate.

6

Easements can be created in a number of ways

including easement by express grant, easement by prescription, and easement by implication of

law or necessity.

7

1. Easements by Express Grant

Express easements can be created by contract, deed or other written instrument.

8

To

create an express easement, the written instrument must describe with reasonable particularity

the land to which the easement extends.

9

It is not, however, necessary to delineate the exact path

and boundaries of the easement, i.e., provide a legal description of the easement.

10

The

description of an easement is sufficient if it provides a key so that the land where the easement is

located can be identified.

11

An easement description has been found sufficient in the following

situations:

• easement was described as being situated “between Lot #77, Lake George and

Pine Avenue, including causeway to the creek, near the railroad bridge, known

as the headwaters of the Gress River” was held to be sufficient.

12

5

5 Rest. of Law, §§ 450, p. 2901, 540b, p. 2903; Sinnett v. Werelus, 83 Idaho 514, 365 P.2d 952

(1961); Young v. Thendara, Inc.

, 328 Mich. 42, 43 N.W.2d 58 (1950); Kazi v. State Farm Fire

and Cas. Co., 24 Cal. 4

th

871, 15 P.3d 223 (2001); Preseault v. U.S., 100 F.3d 1525 (Fed. Cir.

1996); Sun Valley Land and Minerals, Inc. v. Hawkes

, 138 Idaho 543, 66 P.3d 798 (2003).

6

25 Am. Jur. 2d, Easements and Licenses § 15.

7

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-1; Jones v. Mauldin, 208 Ga. 14, 64 S.E.2d 452 (Ga., 1951) overruled on

other grounds.

8

Latham Homes Sanitation, Inc. v. CSX Transportation, Inc., 245 Ga.App. 573, 538 S.E.2d 107

(2000); Bibb County v. Georgia Power Co.

, 241 Ga.App. 131, 525 S.E.2d 136 (1999); Khamis

Enterprises, Inc. v. Boone, 480 S.E.2d 364 (1997); Irvin v. Laxmi, 266 Ga. 204, 467 S.E.2d 510

(1996); City of Columbia, Mo. v. Baurichter

, 729 S.W.2d 475 (Mo. Ct. App. 1987); Lewis v.

DeKalb County, 251 Ga. 100, 303 S.E.2d 112 (1983); Georgia Power Co. v. Leonard, 187 Ga.

608, 1 S.E.2d 579 (1939); Seaboard Air Line Ry. Co. v. Greenfield

, 128 S.E. 430 (1925);

Chapman v. Gordon

, 29 Ga. 250 (1859).

9

Lovell v. Anderson, 242 Ga.App. 537, 530 S.E.2d 233 (2000); Concerned Citizens v. State Ex.

rel. Rhodes, 329 N.C. 37, 404 S.E.2d 677 (1991); Champion v. Neason, 220 Ga. 15, 136 S.E.2d

718 (1964); Lewis v. Bowen

, 209 Ga. 717 (1), 75 S.E.2d 422 (1953); Rest. of Law, § 471(d), p.

2964.

10

Wynns v. White, 273 Ga.App. 209, 614 S.E.2d 830 (2005); Murdock v. Ward, 267 Ga. 303,

477 S.E.2d 835 (1996).

11

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-1; Howard v. Rivers, 266 Ga. 185, 465 S.E.2d 666 (1996); Glass v. Carnes,

260 Ga. 627(4), 398 S.E.2d 7 (1990); Champion v. Neason

, 220 Ga. 15, 136 S.E.2d 718 (1964).

12

Wynns v. White, 273 Ga.App. 209, 614 S.E.2d 830 (2005); Adams v. City of Ila, 221 Ga.App.

372, 471 S.E.2d 310 (1996)(property description was sufficient in deed granting right-of-way;

deed contained sufficient “keys” to clarify any indefiniteness in property description, making

reference to militia district in which right-of-way was located, and defining right-of-way

specifically by referring to and incorporating street’s preexisting roadway).

33

• easement was described by a specific reference to a diagram or plat showing

the easement has been held sufficient.

13

• easement represented by parallel lines on plat of subdivision.

14

However, the grant of an easement with an indefinite description will be upheld where its

location has been established by parties’ consent.

15

Moreover, in instances where the written

instrument is ambiguous, parol evidence may be used to explain the extent of the description of

an easement and identify its location.

16

For example, in a situation where a plat is referenced in

a written instrument purporting to grant an easement, but where no plat is actually attached to the

written instrument, parol evidence identifying the plat may be introduced.

17

2. Easements by Prescription

In Georgia, the elements of a prescriptive easement are essentially the same as adverse

possession.

18

Prescription, however, differs from adverse possession;

19

adverse possession

confers title to the property while prescription only confers the right to use the property.

20

The person seeking to establish prescriptive easement must prove that the use or the road

or way was public, continuous, exclusive, uninterrupted (7 years for improved lands or 20 years

through wild lands), peaceable, and accompanied by a claim of right.

21

Moreover, the use must

be adverse (i.e., without the consent of the owner) rather than permissive, the private way must

not exceed 20 feet in width and be the same 20 feet as originally appropriated, and must be kept

in repair during the period of use.

22

13

Howard v. Rivers, 266 Ga. 185, 465 S.E.2d 666 (1996); Chicago Title Insurance Co. v.

Investguard, Ltd., 215 Ga.App. 121, 449 S.E.2d 681 (1994)(access easement may be described

by reference to a plat showing a road lineated on the plat, which plat is attached to a deed and

incorporated by reference into the deed); Turner v. City of Nashville

, 177 Ga.App. 649, 340

S.E.2d 619 (1986); Norton Realty & Loan Co. v. Board of Education.

, 129 Ga.App. 668(4), 200

S.E.2d 461 (1973).

14

Chicago Title Insurance Co. v. Investguard, Ltd., 215 Ga.App. 121, 449 S.E.2d 681 (1994);

Hardigree v. Hardigree

, 244 Ga. 830, 262 S.E.2d 127 (1979).

15

Barton v. Gammell, 143 Ga.App. 291, 238 S.E.2d 445 (Ga.App. 1977)(The grant of an

easement containing an indefinite description will be upheld where its location has been

established by consent of the parties).

16

Irvin v. Laxmi, 266 Ga. 204, 467 S.E.2d 510 (1996).

17

Mayor & Council of Athens v. Gregory, 231 Ga. 710, 203 S.E.2d 507 (1974).

18

Moody v. Degges, 258 Ga.App. 135, 137, 573 S.E.2d 93, 95 (2002).

19

Thomson v. Dypvik 174 Cal App 3d 329, 220 Cal.Rptr. 46 (6

th

Dist., 1986); Wheeler v.

Newman, 394 NW2d 620 (Minn App., 1986); Glenville v Strahl, 516 SW2d 781(Mo App.,

1974).

20

Id.

21

Moody v. Degges, 258 Ga.App. 135, 137, 573 S.E.2d 93 (2002); Jackson v. Norfolk Southern

R.R., 2002, 255 Ga.App. 695, 566 S.E.2d 415 (2002); Childs v. Sammons, 272 Ga.App. 737,

739(2), 534 S.E.2d 409 (2000); O.C.G.A. § 44-9-1.

22

Id.

34

Merely using a roadway, however, is insufficient to acquire a prescriptive easement.

23

Moreover, since the imposition of prescriptive rights is a rather harsh remedy, Georgia courts

will strictly construe the elements of OCGA § 44-9-1 against the party asserting the right to the

easement.

24

If the party seeking the prescriptive easement fails to strictly comply with OCGA §

44-9-1 or fails to prove any of the necessary elements to establish prescriptive rights, he will not

be entitled to acquire the easement.

25

Further, where a road has been used prescriptively as a private way for as much as one

year, the owner of land over which it passes (i.e., the servient estate) may not close it up without

first giving the users thereof thirty days’ written notice so that they may have the way made

permanent.

26

3. Easements by Necessity

Under O.C.G.A. § 44-9-40(b), “[w]hen any person or corporation of this state owns real

estate or any interest therein to which the person or corporation has no means of access, ingress,

and egress and when a means of ingress, egress, and access may be had over and across the lands

of any private person or corporation, such person or corporation may file his or its petition in the

superior court of the county having jurisdiction…”

27

Even where other means of access exist,

condemnation of a private way or easement by necessity is warranted if the easement seeker can

establish that the existing access options are not economically feasible.

28

To be entitled to condemn an easement or private road over the lands of another by

necessity, the easement seeker must show that the way sought by him is absolutely indispensable

as a means for reaching his property.

29

The way of necessity must be more than one of

convenience.

30

A landowner seeking to establish an easement by necessity will not be entitled to a

private way of necessity to obtain access if he voluntarily landlocked himself; i.e, he created the

problem he now seeks redress for.

31

The reasoning behind the rule is that a private way would

only reward the property owner for his own negligence in failing to reserve an easement for

23

BMH Real Estate Partnership v. Montgomery, 246 Ga.App. 301, 304(3), 540 S.E.2d 256

(2000).

24

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-54; In re Popescu, 172 B.R. 691 (1994)(under Georgia law, establishment of

private way by prescription is to be strictly construed); Farris Construction Co. v. 3032 Briarcliff

Road Associates, 247 Ga. 578, 277 S.E. 2d 673 (1981).

25

Id.

26

Hall v. Browning, 195 Ga. 423, 24 S.E.2d 392 (1943); Kirkland v. Pitman, 122 Ga. 256, 50

S.E. 117 (1905).

27

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-40(b); Hensley v. Henry, 246 Ga.App. 417, 541 S.E.2d 398 (2000).

28

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-40; Atlanta-East, Inc. v. Tate Mountain Associates, Inc., 265 Ga. 742, 462

S.E.2d 613 (1995).

29

Wyatt v. Hendrix, 146 Ga. 143, 90 S.E. 957 (1916).

30

Moore v. Dooley, 240 Ga. 472, 241 S.E.2d 232 (1978); Hasty v. Wilson, 223 Ga. 739, 158

S.E.2d 915 (1967); Burton v. Atlanta & W.P.R. Co.

, 206 Ga. 698, 58 S.E.2d 424 (1950).

31

Bruno v. Evans, 200 Ga.App. 437, 408 S.E.2d 458 (1991), certiorari denied.

35

property he had previously sold.

32

However, even where a party has voluntarily landlocked

himself, under some circumstances, he may still be entitled to obtain access by condemnation

under O.C.G.A. § 44–9–40(b) if he can show that construction of a road over the property sold

would cost more than the value of the remaining property.

33

C. Difference between Easements and Fee Estates, Restrictive Covenants and Licenses

The difference between a fee simple estate and an easement is that the easement describes

the right to the use of the land, while title to the fee simple estate is the grant of title to the land

itself. This difference is not insignificant because a fee simple estate owner receives substantive

and procedural rights that are not to easement holders. For example, the owner of a fee simple

estate, unlike an easement, has the right to sell his land.

34

In determining whether the interest

conveyed is easement or fee simple title to land, each case depends upon its own particular facts

and circumstances.

35

As with many determinations involving real property, this determination

turns on the intent of the parties.

36

Easements also differ from restrictive covenants. Unlike restrictive covenants, easements

require only that the servient estate owner not to interfere with the dominant estate owner’s

rights.

37

Easements “run with the land”, which means that subsequent owners or successors may

either be able to enforce the easement or be burdened by it.

38

A restrictive covenant, on the

other hand, may or may not run with the land and it generally sets limits upon the use of the

subject property. A restrictive covenant relates to the burden or servitude upon land, an

easement relates to the benefit conferred upon the dominant tenement.

39

Whether an instrument

grants an easement or a restrictive covenant depends on the intent of the parties and an

evaluation of the whole instrument in light of the facts and circumstances at the time of its

execution.

40

For example, where a deed specifically states that the land was sold and conveyed

subject to specified restrictions, a restrictive covenant rather than an easement will be found; the

presence of the word “restrictions” was indicative of the intent of the grantor to restrict the use of

the property rather than grant an easement.

41

Easement are also distinguishable from licenses in that a licenses are mere permissive

uses which confer a personal privilege to do some act on the land without possessing an actual

estate in that land and they are generally revocable.

42

An easement, on the other hand, implies

32

Mersac v. National Hills Condominium Association, 267 Ga. 493, 480 S.E.2d 16 (1997).

33

Kellett v. Salter, 244 Ga. 601, 261 S.E.2d 597 (1979).

34

Lanier v. Burnette, 245 Ga.App. 566, 538 S.E.2d 476 (2000).

35

Barber v. Southern Ry. Co., 247 Ga. 84, 274 S.E.2d 336 (1981); Jackson v. Rogers, 205 Ga.

581, 54 S.E.2d 132 (1949); Georgia & F. Ry. v. Swain

, 145 Ga. 817, 90 S.E. 44 (1916).

36

City of Buford v. Gwinnett County, 262 Ga. 248, 585 S.E.2d 122 (Ga.App. , 2003).

37

Brown v DOT, 195 Ga.App. 262, 393 S.E.2d 36 (1990).

38

Barton v. Gammell, 143 Ga.App. 291, 238 S.E.2d 445 (Ga.App. 1977).

39

Id.

40

O.C.G.A. § 44-5-34.

41

Moreland v Henson, 256 Ga 685, 353 S.E.2d 181 (1987).

42

Barton v Gammell, 143 Ga.App. 291, 238 S.E.2d 445 (1977).

36

an interest in the land in and over which it is to be enjoyed, and are generally not revocable.

43

D. Scope of Easements

Where an easement is granted without limitations on its use, an easement owner is

entitled to use an easement for all reasonable purposes that develop over time if such uses

significantly relate to the purpose the easement was granted.

44

The first rule of construction in

examining the scope and purpose of an easement is to look at the intent of the parties.

45

In Savannah Jaycees Foundation, Inc. v. Gottlieb, subdivision lot owners were authorized

to park their automobiles on property designated as a park in the subdivision plat, as incident to

their easement to use the park property for recreational purposes;

46

implicit in the easement grant

was the authority to do things reasonably necessary for enjoyment of the easement, recreational

users of property.

47

Notwithstanding, the owners of the servient estate did have the power to

restrict which portions of property could be used for parking since unlimited parking rights were

unnecessary for enjoyment of the easement.

48

In Reece v. Smith, owners of landlocked property who acquired an implied easement

were authorized to install within path of easement, underground utilities since utilities were

necessary to reasonable enjoyment of the landlocked land in question as place of residence, and

there was no evidence that installation would unreasonably burden the servient landowners’

rights.

49

However, in Lanier v. Burnette, where landowners had acquired an easement for the

sole purpose of ingress to and egress from the property, they were not entitled to a utility

easement because, under the particular circumstances, it was not a reasonable use that

significantly related or was essential to the deed-granted easement.

50

E. Abandonment or Forfeiture, Extinguishment and Estoppel of Easements

An easement may be lost or extinguished in a number of ways including abandonment or

forfeited by nonuse, and estopppel.

51

An easement of necessity may also be extinguished where

43

Barton v Gammell, 143 Ga.App. 291, 238 S.E.2d 445 (1977).

44

Kiser v. Warner Robins Air Park Estates, Inc., 237 Ga. 385, 228 S.E.2d 795 (1976); Savannah

Jaycees Foundation, Inc. v. Gottlieb, 615 S.E.2d 226 (2005).

45

Kiser v. Warner Robins Air Park Estates, Inc., 237 Ga. 385, 228 S.E.2d 795 (1976).

46

Savannah Jaycees Foundation, Inc. v. Gottlieb, 273 Ga.App. 374, 615 S.E.2d 226 (2005).

47

Id.

48

Id.

49

Reece v. Smith, 265 Ga.App. 497, 594 S.E.2d 654 (2004).

50

Lanier v. Burnette, 245 Ga.App. 566, 538 S.E.2d 476 (2000).

51

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-6; Owens Hardware Co. v. Walters, 210 Ga. 321, 80 S.E.2d 285 (1954);

Tietjen v. Meldrim

, 169 Ga. 678, 151 S.E. 349 (1930); Rolleston v. Sea Island Properties, Inc.,

1985, 254 Ga. 183, 327 S.E.2d 489, certiorari denied 106 S.Ct. 77, 474 U.S. 823, 88 L.Ed.2d 63

(an easement can also be extinguished by estoppel if the easement owner shows an intent not to

make use of the easement in the future, and the servient estate owner reasonable relies upon the

conduct of the dominant owner).

37

the purpose for the easement ceases to exist.

52

The owner of an easement may abandon or forfeit an easement if he abandons or fails to

use it for “a term sufficient to raise the presumption of release or abandonment”. There is,

however, no presumption of abandonment from nonuse for a period of time less than 20 years.

53

Moreover, the mere non-use of an easement acquired by grant, even for a time period greater

than 20 years, without further evidence of an intent to abandon it, will not be considered

abandoned.

54

Intent to abandon an easement can only be established with clear, unequivocal and

decisive evidence.

55

Intent can also, however, be inferred from acts of the parties.

56

For

example, sufficient evidence existed to extinguish an easement where an easement was not used

for approximately 30 years and a fence had been built barring access to the easement, and it had

been shown that the easement owner had been present at the property and therefore could have

used the easement or objected to the presence of the fence.

57

An easement can also be extinguished by estoppel if the easement owner shows an intent

not to make use of the easement in the future, and the servient estate owner reasonable relies

upon the dominant owner’s conduct.

58

To determine whether an easement is properly

extinguished by estoppel, one must ascertain whether it was reasonably foreseeable that the

servient owner would rely upon the easement owner’s actions, and whether reinstatement of the

easement would unreasonably harm the servient owner.

59

It is, also, well-settled that an easement of necessity may be extinguished where the

purpose for the easement ceases to exist.

60

For example, where credible evidence is presented

that other access to the property is available, a way of necessity will cease to exist.

61

F. Maintenance and Repair of Easements

The easement owner ordinarily has a duty to maintain or repair an easement, where the

52

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-5; Reece v. Smith, 265 Ga.App. 497, 594 S.E.2d 654 (2004), reconsideration

denied, certiorari denied.

53

Boling v. Golden Arch Realty Corp., 242 Ga. 3, 4, 247, S.E.2d 744 (1978).

54

Smith v. Gwinnett County, 248 Ga. 882(2), 286 S.E.2d 739 (1982); Church of the Nativity,

Inc. v. Whitener, 249 Ga.App. 45, 547 S.E.2d 587 (2001), reconsideration denied. (non-use of

express easement over church’s property for 24 years did not constitute abandonment of

easement, where current easement holders’ predecessors in title had no intent to abandon

easement).

55

Hardigree v. Hardigree, 244 Ga. 830(2), 262 S.E.2d 127 (1979).

56

Tietjen v. Meldrim, 172 Ga. 814, 159 S.E. 231 (1931).

57

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-6; Duffy Street S.R.O., Inc. v. Mobley, 266 Ga. 849, 471 S.E.2d 507 (1996).

58

Rolleston v. Sea Island Properties, Inc., 254 Ga. 183, 327 S.E.2d 489 (1985), certiorari denied

106 S.Ct. 77, 474 U.S. 823, 88 L.Ed.2d 63

59

Id.

60

Reece v. Smith, 265 Ga.App. 497, 594 S.E.2d 654 (2004), reconsideration denied, certiorari

denied.

61

Russell v. Napier, 82 Ga. 770, 9 S.E. 746 (1889).

38

easement is used for his benefit alone.

62

This duty arises both statutorily

63

and by caselaw.

64

It

is implicit with the grant of an easement that the easement holder will undertake those things

reasonably necessary for and ancillary to the continued use and enjoyment of the easement.

65

With the requirement for the easement owner to maintain and keep the easement in repair also

comes the power to restrict the unauthorized use of that easement;

66

this despite the fact that the

easement owner does not actually own the property in fee.

67

An easement owner is responsible for repairs when use of easement is impaired due to

lack of maintenance.

68

An easement may be forfeited if the easement owner fails to properly

maintain or repair the easement.

69

It is, however, more likely that the easement owner would be

assessed damages, as opposed to forfeiture, since equity seeks to avoid the drastic measure of

forfeiture.

70

Moreover, one seeking a prescriptive easement must show that he made repairs and

maintenance for the prescriptive period.

71

The purpose of requiring a showing of repairs is to

give notice to the landowner that the prescriber’s use of the road is adverse rather than

permissive.

72

G. Creation of Private Roads through Condemnation

In Georgia, private condemnation is authorized by statute, specifically O.C.G.A. § 44-9-

40 et seq.

73

Under section 44-9-40, the county superior courts are vested with the authority and

jurisdiction to grant private ways or easements to individuals to enter and exit their property or

62

Kiser v Warner Robins Air Park Estates, Inc., 237 Ga 385, 228 S.E.2d 795 (1976).

63

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-40 (easements shall be kept “…in repair by the person on whose application

they are established or his successor in title”); O.C.G.A. § 44-9-43 (“the condemnor or his

successors in title have a duty to maintain the private way…and in a state of good repair”).

64

Lanier v. Burnette, 245 Ga.App. 566, 538 S.E.2d 476 (2000). The servient estate owner, on

the other hand, is not legally obligated to maintain or repair an easement for the benefit of an

easement owner. Harvey v. Lindsey

, 251 Ga.App. 387 (2001).

65

Lanier v. Burnette, 245 Ga.App. 566, 538 S.E.2d 476 (2000). The servient estate owner, on

the other hand, is not legally obligated to maintain or repair an easement for the benefit of an

easement owner. Harvey v. Lindsey

, 251 Ga.App. 387 (2001).

66

Sams v Young, 217 Ga 685, 124 S.E.2d 386 (1962).

67

Id.

68

Equitable Life Assur. Soc. of U. S. v. Tinsley Mill Village, 249 Ga. 769, 294 S.E.2d 495

(1982).

69

Kiser v Warner Robins Air Park Estates, Inc., 237 Ga 385, 228 S.E.2d 795 (1976).

70

Id.

71

Mersac, Inc. v. National Hills Condominium Ass’n, Inc., 267 Ga. 493, 480 S.E.2d 16 (1997),

reconsideration denied, (Feb. 14, 1997).

72

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-54 Lopez v. Walker, 250 Ga.App. 706, 551 S.E.2d 745 (2001),

reconsideration denied, (July 2, 2001) and cert. denied, (Jan. 9, 2002); Simmons v. Bearden

, 234

Ga.App. 81, 506 S.E.2d 220 (1998)(the requirement that the plaintiff has kept the way in repair

is not so much the repairs as the notice which is given by the repairs).

73

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-40.

39

places of business under certain circumstances.

74

Such easements, however, must be 20 feet or

less in width depending on the particular needs of the applicant.

75

Any person or corporation with landlocked property may file in the superior court in the

county where the property sits a petition for ingress, egress, and access over and across the lands

of any private person or corporation in order to access there property.

76

Each such petition is

deemed a declaration of necessity by the applicant and must allege such facts and pray for a

judgment condemning an easement of access, ingress, and egress not to exceed 20 feet in width

over and across the property of the private person or corporation.

77

Additionally, each petition

must describe the property over which the easement is sought with particularity and must include

the following:

• the distance and direction of the easement;

78

• the nature of any improvements through which the private way will go;

79

• a plat showing the measurements and location of the easement;

80

• the names and addresses of all persons owning an interest in the property.

81

The applicant must also ensure that a copy of the petition and any attachments is served upon all

known persons with an ownership interest in the property and who reside in the county where the

property is situated.

82

Additionally, the petition must also name an assessor to act on behalf of

the person or corporation seeking to condemn the easement.

83

After taking into consideration the requirements of service, the superior court judge will

make and enter up a “show cause” order requiring the owner or owners of the property show

cause as to why the easement for private way should not be condemned and requiring the said

owner or owners to name an assessor to act on his or their behalf.

84

The owner of the property

that has been condemned, however, may challenge necessity, location, and width of private way,

and can, also, extinguish all claims to private way if party seeking way fails to timely pay

adequate compensation.

85

74

Id.

75

Id.

76

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-40(b).

77

Id.

78

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-41(1).

79

Id.

80

Id.

81

Id.

82

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-41.

83

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-42.

84

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-43.

85

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-47; Cline v. McMullan, 263 Ga. 321, 431 S.E.2d 368 (1993).

40

Once the private easement is established, “it shall be entered on and fully described on the

official minutes of the county commission and the road deed file”.

86

Moreover, once the

condemnation of the private easement becomes final, the condemnor has a duty to maintain the

private way and to keep it open and in a state of good repair.

87

Failure to maintain the private

way and to keep it open and in a state of good repair for a period of one year will constitute an

abandonment of the private way, and the title shall revert back to the owner of the property over

which the private easement was condemned or his successors in title.

88

Those individuals whose

property has been condemned for the creation of a private easement are entitled to fair and just

compensation by the condemnor for the taking of their property, the amount of which is to be

determined by a jury.

89

To prevail on summary judgment in a private way condemnation action, the landowner

opposing the condemnation must present evidence that the one seeking condemnation has a

reasonable means of access to its property other than over landowner’s property.

90

86

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-50.

87

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-41.

88

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-41.

89

O.C.G.A. § 44-9-46.

90

O.C.G.A. §§ 9-11-56(c), 44-9-40; Atlanta-East, Inc. v. Tate Mountain Associates, Inc., 265

Ga. 742, 462 S.E.2d 613 (1995).

41

42

Abandonment And Vacation Considerations

Submitted by Dale (Bubba) R. Samuels

• Abandonment Of Public Roads

• Termination Of Private Easements

43

III. ABANDONMENT AND VACATION CONSIDERATIONS

A. Abandonment of Public Roads

Once duly created and made a part of a public road system pursuant to O.C.G.A. § 32-4-1

et

seq., a public road may be abandoned pursuant to the procedures set forth in O.C.G.A. § 32-7-

1 et

seq. The road abandonment statute essentially provides a two-step process for removing a

public road from the public entity’s road system as follows: first, the public road must be

declared abandoned,

1

and once abandoned, the statute sets forth the methods of disposition of the

abandoned roadway.

2

1. When should statutory vacation be initiated?

O.C.G.A. § 32-7-1 provides the authority for the State, counties, and municipalities to

substitute for, relocate, or abandon public roads, pursuant to the procedure for abandonment set

forth in O.C.G.A. § 32-7-2. Thus, whenever the road to be abandoned constitutes a “public

road,” the statutory abandonment procedure must be utilized. See

, Forsyth County v.

Martin, 279 Ga. 215, 610 S.E.2d 512 (2005).

a. Authority to vacate public roads

The road abandonment statute specifically provides as follows:

Whenever deemed in the public interest, the department or a county or a

municipality may substitute for, relocate, or abandon any public road that

is under its respective jurisdiction, provided that a county or municipality

1

O.C.G.A. § 32-7-1 provides the authority of the State, counties, and municipalities to substitute

for, relocate, or abandon public roads. O.C.G.A. § 32-7-2 sets forth the procedure to be followed

in exercising that authority.

2

O.C.G.A. § 32-7-3 provides the authority for the State, counties, and municipalities to dispose

of property no longer needed for public road purposes. O.C.G.A. § 32-7-4 sets forth the

procedure to be followed in disposing of such property. Finally, O.C.G.A. § 32-7-5 provides for

the continued use, maintenance, and improvement of the abandoned road, as well as the authority

to lease the abandoned road to third parties, for other purposes.

44

shall first obtain the approval of the department if any expenditure of

federal or state funds is required.

Thus, the threshold inquiry involves a determination by the pertinent governing authority

3

of the

public interest to be served by the substitution, relocation,

4

or abandonment of the public road.

Additionally, if any expenditure of state or federal funds is involved in the substitution,

relocation, or abandonment of the public road, the statute requires that a county or municipality